Where the Humanities Are Thriving

Speakers

Sarah Guyer

Dean of the Division of Arts and Humanities

University of California at Berkeley

Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr.

Associate Professor

Austin Community College, Texas

Melinda Zook

Director, Cornerstone Integrated Liberal Arts Program

College of Liberal Arts

Purdue University

Ian Wilhelm (moderator)

Deputy Managing Editor

The Chronicle

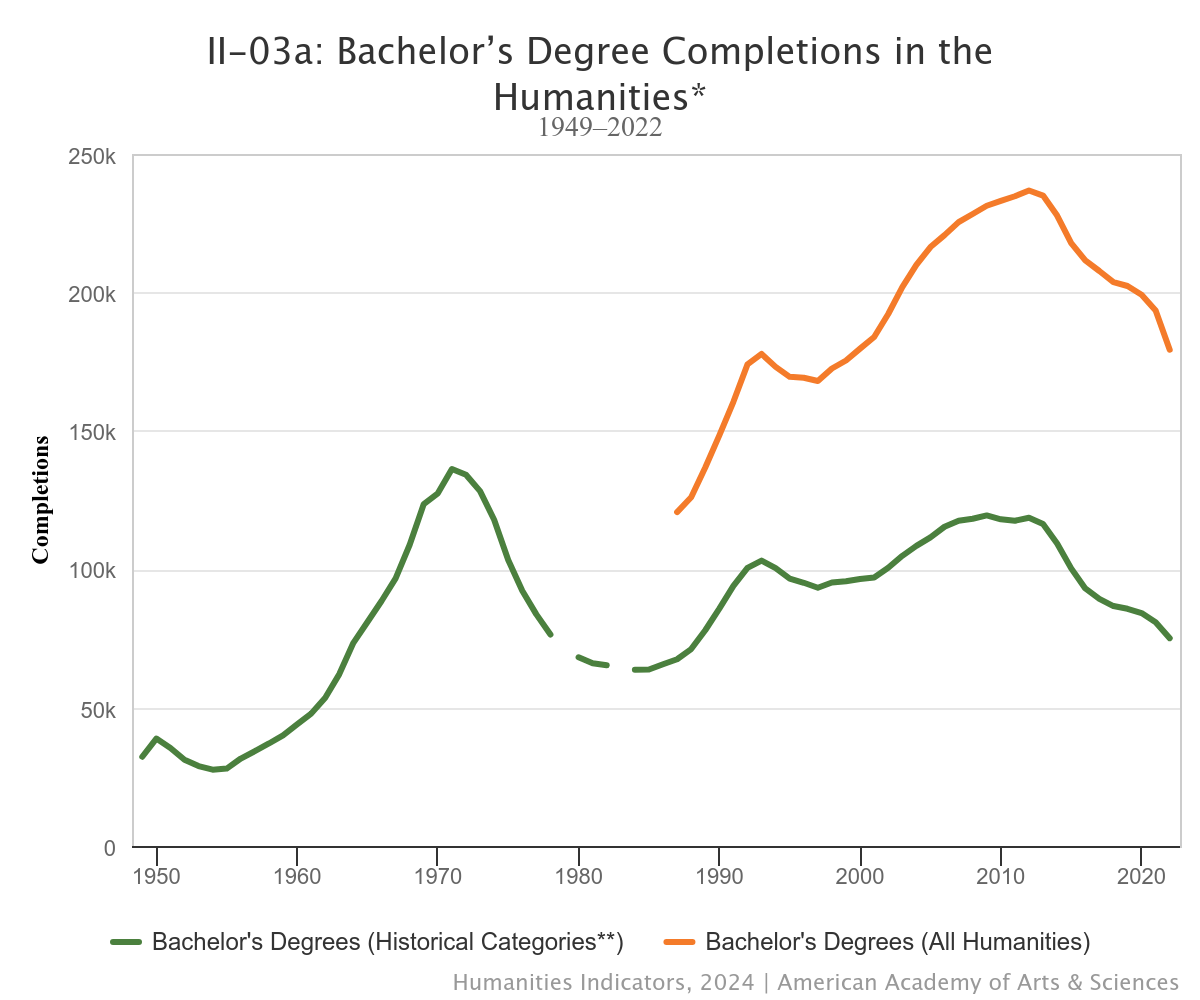

The humanities are in a crisis, or at least that's the prevailing narrative. We’ve seen the headlines — and indeed, there are serious signs of concern. The number of undergraduates earning humanities degrees has dropped significantly in the last decade or so.

During that past decade the number of humanities degrees awarded fell by 24 percent from 2012 to 2022, and the study of English and history at colleges has fallen by about a third, according to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Humanities Indicators project. And many colleges, of course, are under financial and enrollment strains, and seeking to shrink, or sometimes even close, humanities departments where student interest has waned.

There are a lot of reasons for this. One of the usual culprits is the Great Recession of 2007 and 2008. After that, college students have become more focused on courses and degrees that they think lead to better careers and job outcomes. Another culprit is technology, like the iPhone. People say it’s distracted us from engaging in deep reading and engaging in literature, history, and art. Some say generative AI may be making skills like writing seem less important to students.

To be sure, the reasons for the declining interest are nuanced and complex.

Yet at some institutions, student enrollment and appreciation for the humanities has grown. What can we learn from these examples? What does it mean for the possibility of rewriting this frequent, if easy, narrative, that the humanities are in a freefall?

To explore these questions, The Chronicle held a virtual forum, “Where the Humanities Are Thriving,” on October 2, with an expert panel offering advice to help strengthen messaging, modernize course offerings, and revive interest in this field of study. The following comments, edited for clarity and length, represent key takeaways from the forum. To hear the full discussion, watch the recording here.

Ian Wilhelm: Melinda, Purdue has the reputation of being a science and engineering school. It certainly has a strong liberal-arts and humanities program, but from 2011 to 2015, the college saw a 37-percent drop in humanities majors, and the share of undergraduates taking humanities courses had also declined. But that situation has turned around. Can you give us the origin story of that and explain how the program works?

Melinda S. Zook: After the recession of 2008, we had a steep dive in our enrollments in the College of Liberal Arts. Before then, we were doing just fine, and then it just got worse and worse — to the point where we were just canceling courses. We needed to do something big and bold. So in 2016, the dean, David Reingold, charged me with the Cornerstone program. Basically, it started as an integrated liberal-arts program. We were going to bring the liberal arts to the rest of the students, because the rest of the campus was thriving. Our enrollments at Purdue were extremely healthy.

We decided that we needed some way to bring them in a gateway sequence. So what we did, which was kind of risky, was take our full-time faculty and have them teach our gen. ed courses — a sequence that teaches oral and written communication, and transformative texts. We made this sequence very appealing to attract faculty members. It's hard to take a scholar and say, Look, you're not going to be teaching Nietzsche anymore. Well, you can still teach that, but much less. You're going to also be teaching a gen. ed. course.

But the faculty also knew that we needed to do something, and transformative texts was attractive. You could teach the course you always wanted to teach. The books, the poetry, the drama you always wanted to teach. And we scaled up teaching from about 100 students that first year to the place that we are now, which is teaching 5,400 students in the gateway sequence.

Why is this important? Because you have to have an on-ramp to the liberal arts. You have to have some way of bringing them, showing them what we do. You need to talk about, and show them, the beauty of literature, philosophy, and history.

And the best evidence that this is working is not just the sheer number of students that we're teaching now, but the fact that we have hired over 100 faculty in the last three years in the College of Liberal Arts, and are hiring again this year.

Wilhelm: You also offer a certificate, right?

Zook: We have a 15-hour certificate program. The themes of the classes are very STEM-oriented. So you could do a certificate in science and technology, or health care and medicine, or environment and sustainability. What we're hoping is that students in, say, engineering, will do the certificate to round out their education, because even though the gateway sequence is great, they need more liberal-arts courses to really improve their communication skills and their knowledge of the world.

So the certificate has been successful, too. There are a few 100 every semester, and that's about all you need.

Wilhelm: Ted, you have the Great Questions program. It's notable that it's thriving at a community college, given the stereotype that community colleges are mostly for vocational technical education — when [the education] is much more broad than that. Can you tell the origin story of the Great Questions program, and what interest you've seen?

Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr: We've taken a collegewide requirement for a first-year student-success seminar, and we infuse the study of the humanities in that requirement. We created an alternate curriculum for that course that includes the discussion-based study of transformative texts. That course began in about 2017. We've had almost 5,000 students that have completed Great Questions since that point.

One thing that's unique about the Great Questions seminar is that it has a common curriculum. It’s Week Six, and every single Great Questions class just finished reading [Plato’s] Meno. So the hundreds of students at Austin Community College on our many different campuses in a service area the size of New Jersey just finished reading the Meno today. And that's a really wonderful experience, because in a community college you have such a rich diversity of students. Are they parents? Are they older or younger people coming back for new careers? People who have been in the military, some that have experience in the carceral systems. And you're all seated around the table.

Today we were talking about what virtue is, and can it be taught. What does it mean to be a good person? When students see the humanities as a way to think about their own lives more productively, the humanities become not just the sort of a flourish, something nice to do if you have free time. They become really essential, because all of us have questions about what it means to live a good life. The humanities in general education can help us raise and address those questions more productively. It's not really something that we have an option to not do.

Wilhelm: Sarah, across the University of California system, humanities majors are down, not a huge decline, but somewhat down. But at Berkeley, this is not the case. You are seeing an interesting upward trend. What has made the difference?

Sara Guyer: We asked, How do students find us? Which students are actually on our campus? And we discovered — somewhat alarmingly — that students who intended to major in the arts and humanities weren't even getting accepted. So there's a real front-end question. The amount of work that I would have to do, or others would have to do, to get a student who wasn't interested in the humanities in the first place to become a humanities major is just really hard.

So we asked, Why is it so much harder to get into Berkeley as a student who's interested in the arts and humanities? Can we change that? We have been able to make some difference on that.

We’ve also learned that many of the majors at Berkeley don't exist in high school, and they don't exist in a community college. How does a student know that they want to major in French if their high school doesn't have French, let alone philosophy, let alone what formerly was called classics? Building the on-ramp is really important. We really also invested in making the humanities visible on a campus where STEM and lab research is really visible. It's not always clear what research in the humanities looks like.

Wilhelm: Do these programs need to reframe themselves? Or do they need to be fundamentally rethought how they are taught and fundamentally focused on how they are part of the curriculum?

Hadzi-Antich Jr.: Great Questions is a repurposing of a course, but it also includes a design of the entire college program because it fulfills the student-success requirement for all degrees. We had to create the curriculum redesign, to introduce students to the humanities while helping them develop in the practice and skills that are associated with success at community college.

But then we had to convince the powers-that-be that that fulfilled the student-success requirement as determined by our curriculum advisory committee, and this required us to change or to think about credentialing for this class in a more expansive way.

Guyer: These programs are still grounded in texts. It is something that would have been familiar 10 or 20 or 30 years ago. Maybe the texts have changed, but not the fundamentals. Our curricula isn't radically changed. Our majors aren't radically changed. Over all, our story is the visibility of the humanities, the potential to do research, the fact that there's a future, and that our students are happy. Studies show that the students who major in the humanities are the happiest on campus, and that makes a difference when we're talking about mental-health crises amongst college students.

Zook: We did a lot more than rebranding or repackaging, and it was quite a lift to do the transformative-text sequence. And every degree program at Purdue had to change — every degree. That was some heavy lifting.

Wilhelm: How did you advocate for your programs?

Zook: I went to every single college on campus and asked the dean or associate dean, What do you need from the liberal arts? They wanted their students to have better communication skills. But it wasn't just that — they wanted them to understand the world. They wanted them to broaden their horizons.

The skills-based argument that so many of us make is really problematic. And it was a real turnoff to students. If you talk to students about the humanities, I would talk about how the humanities will change your life. The humanities are inspiring. They will give you new views, and most students, regardless of what all the pundits say, come to college to be changed. They want that experience that will change their lives. They want transcendence, and we have transcendence.

Hadzi-Antich Jr.: Our mission is larger than providing work-force training for private industry. We owe our taxpayers the production of members of our society that are worthy of their sacrifice of tax dollars, and the humanities are the place where that can happen — where students can learn to disagree with each other productively in classrooms. That could be literature classrooms, but also could be political-science classrooms that are taught in a discussion-based environment. The narrative needs to focus on what the public function of a public institution really is, and if all that the public institution is training is for private industry, then that shouldn't be public. The public part of it is rightfully the domain of the humanities.

This Key Takeaways was produced by Chronicle Intelligence. Please contact CI@chronicle.com with questions or comments.

©2024 by The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be reproduced without prior written permission of The Chronicle. For permission requests, contact us at copyright@chronicle.com.