Queensland Shines Light on the Grid

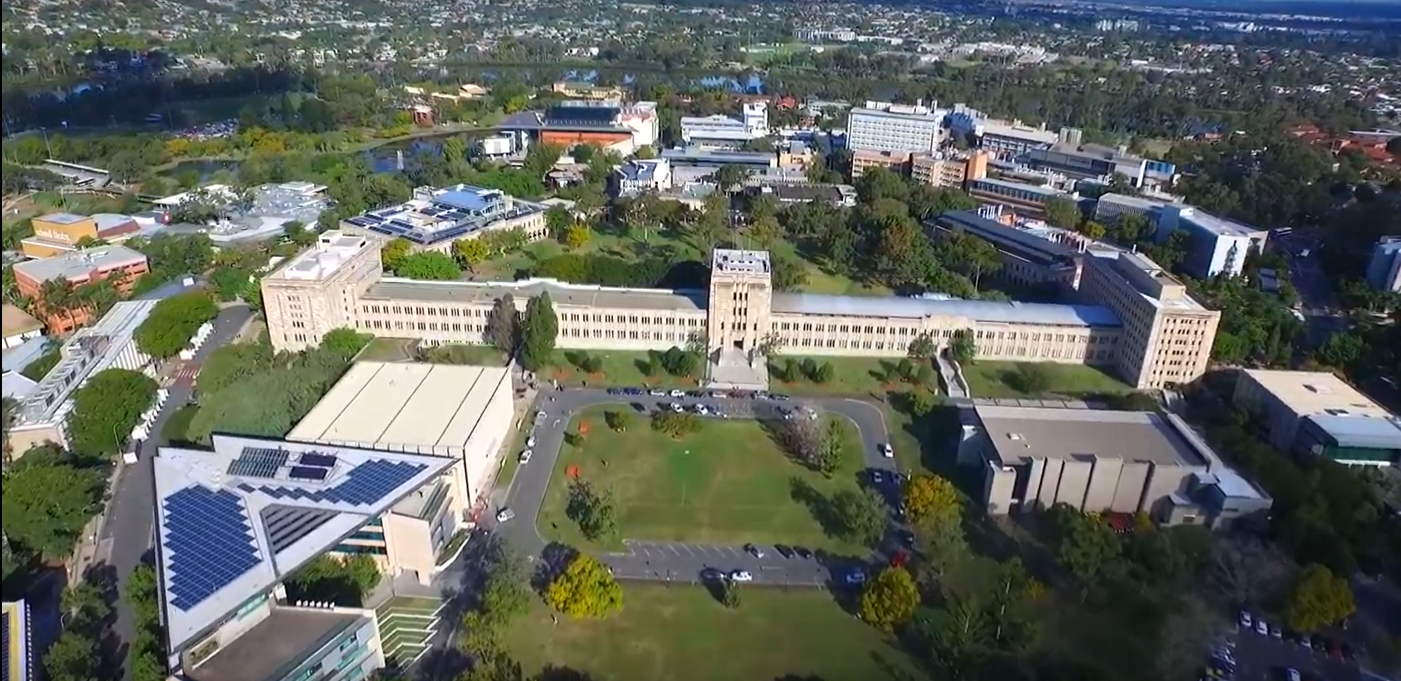

It’s an accomplishment that many academic institutions would envy: The University of Queensland, in northeastern Australia, generates more electricity than it uses each year from its own renewable-energy assets.

“We’re developing new tools and techniques, and new solutions to help power utilities and solar farm owners as well as other stakeholders,” says power-systems expert Professor Tapan Saha, who is among the researchers leading the efforts.

Last year, UQ opened its $A125-million (about $US94-million), 64 megawatt Warwick Solar Farm. Its array of 200,000 solar panels will output about 160 gigawatt hours of energy each year, more than enough to power 25,000 households or reduce coal consumption by 60,000 tons.

That makes UQ a significant “prosumer” — that is, they are both a producer and consumer of energy — particularly in light of the additional six megawatts it produces from its two longer-running installations at its Gatton and St Lucia campuses.

The University would like not only to reduce its power bills, but also to stake a claim to having become a world leader in renewable-energy technologies. In support of this goal, it cites another new initiative: UQ has also opened a new facility for designing and testing power systems. Among the functions of the UQ Industry 4.0 Energy TestLab — a partnership with the German industrial giant Siemens with funding support from the Australian Government — are to find ways both to incorporate renewable power into existing power grids, and to protect power grids from cyber attacks.

About 50 UQ researchers are working in the UQ Renewable Energy Lab and Industry 4.0 Energy TestLab, and the team continues to grow. The more technically oriented among them specialize in such emerging areas as cybersecurity, renewable energy integration, battery energy storage, electric vehicle research and hydrogen application technologies. But the cohort also includes specialists in data science, mathematics, physics, criminology, government policy-making, and business.

The lab’s facilities include a “digital twin” replica of a power system, where researchers can examine, simulate, and test power grids without disrupting or jeopardizing real ones.

Professor Tapan Saha is a global power systems expert, leading the charge in solar energy research

Professor Tapan Saha is a global power systems expert, leading the charge in solar energy research

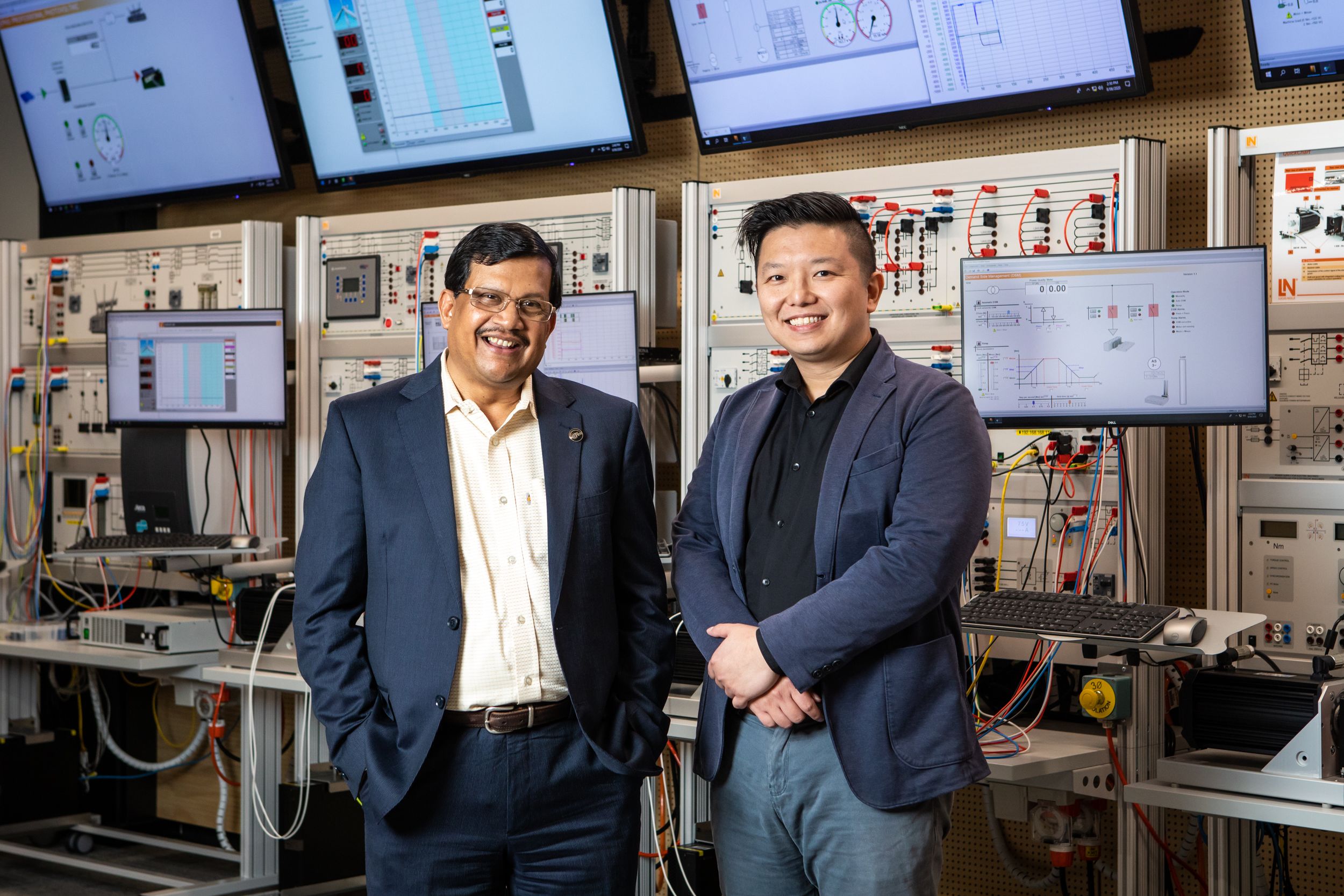

Professor Tapan Saha and Professor Ryan Ko – Professor Ryan Ko is a cybersecurity expert, grappling with the “thorny challenges” related to power grids.

Professor Tapan Saha and Professor Ryan Ko – Professor Ryan Ko is a cybersecurity expert, grappling with the “thorny challenges” related to power grids.

Remarkable Achievements

If UQ officials and researchers don’t say so themselves, their accomplishments are particularly remarkable given that they have come about rapidly. “Even just 10 years ago, Queensland as a state had very little renewables activity,” says Saha, professor of electrical engineering who is leading the UQ Solar initiative, and Energy TestLab with cybersecurity expert Professor Ryan Ko.

A decade ago, Saha and three fellow UQ academics launched a drive that began with placing solar panels on just three university buildings. This drive quickly expanded through campus buy-in, government funding, and industry partnerships.

Late in 2019, Australasian Campuses Towards Sustainability presented UQ with its coveted Green Gown Award for “commitment to sustainability through the Warwick Solar Farm project.” UQ is among more than 500 signatories of the Talloires Declaration of The Association of University Leaders for a Sustainable Future, whose members promote sustainability in teaching, research, operations, and outreach.

Driving the initiative have been two UQ Vice-Chancellor/Presidents, first Professor Peter Høj, from October 2012 to July 2020, and now his successor, Professor Deborah Terry. Høj called the solar farm “an act of leadership that demonstrates that a transition to renewables can be done at scale, [in a way] that’s practicable, and makes economic sense.”

Government resolve, and the state of Queensland’s abundant sunshine, have helped. Australia is shifting rapidly to green energy. In late 2019, for the first time, its main electricity grid was powered, albeit briefly, by 50 percent renewable energy: rooftop solar, wind, large-scale solar, and hydroelectric. Renewables in the country have grown at a per capita rate 10 times the world average. The state of Queensland is particularly attractive for facilities and studies like UQ’s: it has the highest per-capita penetration of rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) facilities in the world, with half a million households already enlisted to capture solar energy.

Among Saha’s roles is supervising the Queensland state government-funded ‘Enabling the Queensland Power Systems of the Future’ project, which was developed to support the technical challenges involved in reaching 50 percent renewable energy by 2030.

UQ’s part in that quest, even before its Warwick Solar Farm and Energy TestLab, included launching, again with industry and government partners, a Solar Enablement Initiative project funded by Australian Renewable Energy Agency to help the energy industry smartly monitor the grid visibility due to massive solar PV penetration. Consistent with the approach of UQ’s new TestLab to investigate microgrid and cyber security, the Solar Enablement Initiative’s aims included helping service providers to be able to monitor how solar panels affect electricity distribution networks.

UQ St Lucia campus generates 70MW of energy annually across its network of rooftop solar arrays

UQ St Lucia campus generates 70MW of energy annually across its network of rooftop solar arrays

A major challenge for energy-grid operators has been that they cannot allow providers of renewables, such as individual households and operators of community wind turbines, to push — and sell — unlimited power into the networks without restrictions. The inputs can disrupt networks with, for example, voltage violations, equipment damage, and tripping.

Those limits on prosumers’ use of solar PV systems, home batteries, and the like have slowed independence from carbon-based fuels. Power grids, Saha explains, were built for a fossil-fuel era when energy flowed in one direction, from power stations to consumers.

He says the bottlenecks could be eased with better data, because businesses and householders are more likely to invest in renewables if they see that standards of research, technology, and implementation are high. Power operators must, then, have much better visibility into their networks, including the complex dynamics of multidimensional reverse power flow, down to highly localized, moment-to-moment flows and fluctuations.

Solar panels at dusk at UQ’s Gatton campus.

Solar panels at dusk at UQ’s Gatton campus.

The UQ Industry 4.0 Energy TestLab at The University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia

The UQ Industry 4.0 Energy TestLab at The University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia

In response to such modern-day challenges and others of “the fourth industrial revolution,” or “Industry 4.0,” the Australian Government has set up TestLabs like UQ’s at six Australian universities. Their remit is to seek solutions in many fields using methods including automation, robotics, machine learning and large-scale data analytics. UQ’s new lab’s piece of that pie is power-system analytics, energy management, microgrids, and cyber security in the emerging era of systems controlled through online technology that make them potentially vulnerable to attacks.

Among UQ’s motivations for operating one of the national TestLabs is that it advances former Vice-Chancellor Høj’s commitment to sharing data from its solar installations with researchers elsewhere, as well as government and industry including commercial operators.

Tapan Saha speaking to the attendees of the UQ’s Industry 4.0 Energy TestLab official launch

Tapan Saha speaking to the attendees of the UQ’s Industry 4.0 Energy TestLab official launch

“We are doing exactly this by providing data from our St Lucia and Gatton solar and battery facilities to many researchers around the world and sharing our findings and publications with them,” says Professor Saha.

Also appealing to UQ, naturally, is that the TestLab’s systems and software allow it to monitor closely its own energy consumption on campus, adjusting power flows as necessary to generate savings.

The TestLab can do all of that, in addition to providing “engaging and deeply realistic teaching and learning experiences for students,” says Vice-Chancellor Terry.

Offerings tied to the new solar farm and TestLab include master’s programs in sustainable energy management and cyber security. The latter is an interdisciplinary program that covers aspects of computer science, geopolitics, ethics, cyber defense, cyber crime, cryptography, and business leadership.

Professor Ryan Ko, Chair and Director of Cyber Security at UQ’s School of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, says both programs are designed around one reality of employment in those fields — offers may come to students well before they complete master’s degrees. That, he says, is because their training is based on real-world issues, with data from actual power installations, working with the kinds of tools and techniques that are in high demand in the renewables sector.

The cybersecurity program, for instance, “has a few exit points,” he says. “If you finish the first six months and find a job, you can leave with a graduate certificate; or you can exit after one year with a graduate diploma.” The further students go, the more they learn about the thorny challenges he grapples with in his own research: how, for example, to untangle all the signals that power-grid operators must decode — some expected, some baffling, some abnormal, some possibly introduced by “malicious actors.”

“UQ is one of the rare universities that has its own full spectrum of all the different energy supply and consumption stages, from solar farms all the way to batteries, all the way to consumption in various buildings.”

And that, he says, allows students not only to see how energy supplies, including “legacy” systems, can be managed with emerging technologies, such as machine learning and artificial intelligence, but also how numerous and varied employment opportunities in the sector have become.

Saha agrees: “Renewables is not only about the technologies; it is also about managing them, and connecting them to the grid. And then sustainability issues, and market challenges. It’s not the traditional electrical power engineering that we used to have 10 or 15 years back. Then, only the big utilities used to employ graduates. Now it is not like that. It is the big utilities, renewable-energy generation companies, commercial service providers, consultants, market operators, battery-storage operators… It’s a big sector, now. And then how do you manage all the data?”

“Our students are having no difficulty in getting jobs, straight away. In fact, some of the bright ones, they are offered multiple jobs,” Ko states.

Read more about UQ's sustainability and cyber security research.

Inside UQ’s Industry 4.0 Energy TestLab, researchers and students can investigate replicas of power systems, called “digital twins”.

Inside UQ’s Industry 4.0 Energy TestLab, researchers and students can investigate replicas of power systems, called “digital twins”.

This content was paid for and created by The University of Queensland. The editorial staff of The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.