NeuroReality™: Using Technology to Make Us More Human

Case Western Reserve University Institute Extends Human Touch—Around the World

On the first day of classes last August, Case Western Reserve University graduate student Luis Mesias held a banana.

Then, when he felt someone else pulling on the fruit, he relaxed his grip and let it go.

As mundane as the moment sounds, it’s one Mesias will never forget.

Because he was in Cleveland, and the banana … was in Los Angeles.

[WRAP-RIGHT] Case Western Reserve University graduate student Luis Mesias

[WRAP-RIGHT] Case Western Reserve University graduate student Luis Mesias

Mesias was part of a demonstration of what Case Western Reserve Biomedical Engineering Professor Dustin Tyler calls NeuroReality™, an approach that applies advanced technology to extend our reach—and increase our humanity. The concept has proved so compelling that Tyler’s team is one of 38 worldwide to qualify for the $10 million Avatar XPrize competition, which aims to create an avatar system that can transport human presence to a remote location in real time.

“The Avatar competition isn’t the end point for us, but it is the embodiment of what we’re trying to do,” Tyler said. “That is, to think about and develop the symbiotic relationship between the machine and the human.”

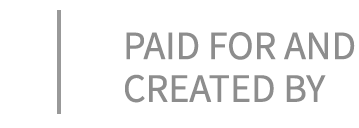

For the Ohio-to-California presentation, Mesias wore a high-tech ring that linked his human hand to a robotic one at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

Without being able to see the device 2,300 miles away, Mesias responded as his California counterpart tapped one of its fingers—“that seems light”—then pressed on it— “hard.”

Later, Mesias relied on the robotic fingers’ feedback to avoid crushing the banana, and also to recognize when to open his hand in response to the UCLA person’s attempt to take it.

“Imagine the next version of emojis,” Tyler said. “Rather than sending a smiley face to your loved one, you can actually reach out and hold their hand.”

From Function to Feeling…

[WRAP-RIGHT]Case Western Reserve Biomedical Engineering Professor Dustin Tyler

[WRAP-RIGHT]Case Western Reserve Biomedical Engineering Professor Dustin Tyler

When Tyler first came to Case Western Reserve as a graduate student nearly three decades ago, his work centered on the use of electrodes to activate nerves—which, in turn, could stir muscles stilled by spinal cord injuries or other damaging events.

In time, he began to apply his expertise to prosthetics for people who had lost limbs—with generous support from federal agencies including DARPA and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Before long, though, he realized that even significantly restoring function would not be enough: A substantial portion of people with powered prosthetics stop using them because the artificial limbs feel so foreign and separate from them.

So Tyler turned his attention to developing ways to provide not just movement but sensation as well.

“The perception of touch actually occurs in the brain, not in the hand itself,” Tyler explained, “so losing the limb is really just losing the switch that turns that sensation on or off.”

The task for Tyler and his colleagues? Finding a way to translate the signals that our limbs send to the brain—say, whether a surface is rough or smooth, an item square or round, or whether the prosthetic limb itself is applying pressure that is heavy, medium or feather-light.

“The electrical stimulation can mimic, come very close to what you have with your normal hand,” Tyler said. “We’ve learned the electrical language to do that.”

For study participant Keith Vonderheuvel of Ohio, the advances meant he no longer had to worry about inadvertently hurting his granddaughter because he could not tell how much pressure he exerted when holding her hand.

“I could actually feel that I was holding her and not squeezing too tight,” he said, “and she gave me a big hug. That one just gets to me.”

For Brandon Prestwood of North Carolina, the moment came when he showed his wife what he could do with the new prosthetic system Tyler’s team developed.

“She reaches out and grabs my [prosthetic] hand,” Prestwood recalled, voice breaking. “In that moment, I was complete. I was whole. … I can't explain in words most of the time how much a simple touch can affect your soul, but for me it does.”

…to Far Broader Application

As Tyler and his team continued to advance technology’s ability to convey human sensation, the researchers and participants alike increasingly recognized the far wider potential of their work. The electronic prosthetic did not have to be directly attached to the individual to send signals to the brain—or to receive them.

“It’s a robotic system, and it can be anywhere,” Tyler said. “I can put your sensors anywhere in the world, and then provide the data back through the same channels. … We can digitize the human experience.”

While many see immense opportunities in such advances, Tyler recognizes others will be wary—understandably so. Such advances have more than scientific implications, but also ones involving ethics, philosophy, privacy, information security, equity of access and more.

To capitalize on opportunities in deliberate and responsible ways, Tyler launched the Human Fusions Institute at Case Western Reserve. In addition to collaborations with UCLA, the institute also involves researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, Cleveland State University, Tuskegee University and University of Wyoming.

Teams are exploring applications in such areas as health care, the military, space and more. While the pandemic has led to dramatic increase in the use of telehealth options, for example, much of medicine still involves physical examination.

“We’re working on this health care avatar concept now,” Tyler explained. “How do we build a remote system where the doctor is now, through neural reality … working with the patient directly?”

For his part, Prestwood imagines surgeons in the U.S. being able to perform life-saving surgeries in third-world countries, or military explosive experts located miles away to use an electronic hand to delicately assess and defuse bombs.

“I want to see this technology improve humankind,” Prestwood said, “not just certain parts or demographics.”

This content was paid for and created by Case Western Reserve University. The editorial staff of The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.