Learning from the Tree of Life: How evolution could help tackle the biggest global challenges

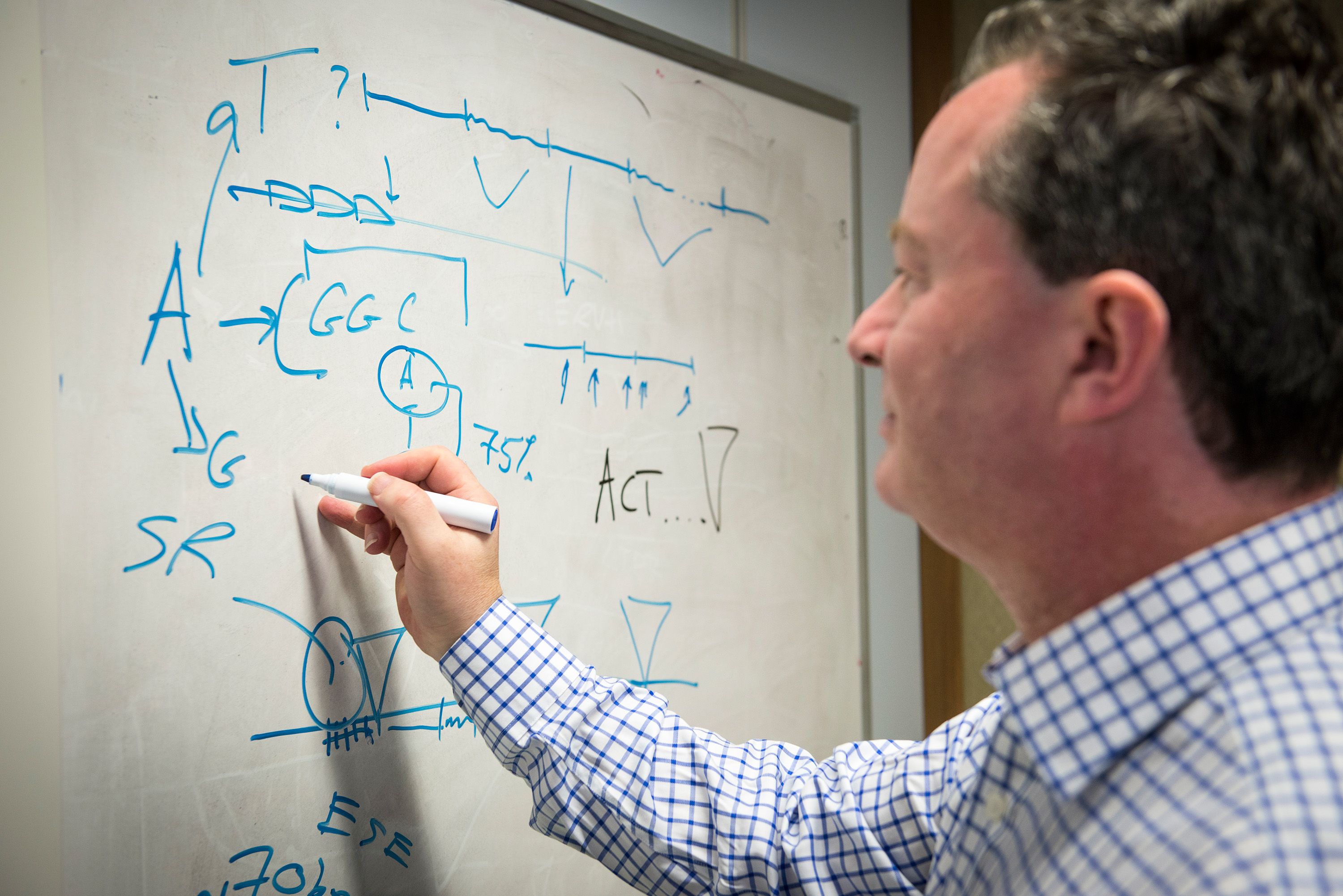

“Evolution is the one theory that unifies the whole of the Life Sciences. The rich diversity of Life on Earth – perhaps 10 million species or more – has a single point of origin over 3.5 billion years ago. This otherwise bewildering variety of molecules and organisms is the result of evolution across a single ‘family tree’ of life. To study living things without knowing evolution is like doing chemistry without grasping the structure of atoms or the nature of the periodic table. Evolution is utterly fundamental to all biology,”

He is the Interim Director of the Milner Centre for Evolution, the UK’s first research centre devoted to studying evolution and applying this fundamental knowledge of biology to tackle today’s global challenges.

The Centre was established in 2018 by outgoing Director Professor Laurence Hurst in partnership with philanthropist, biotech entrepreneur and Bath alumnus Dr Jonathan Milner. The Centre has three core objectives: to ask the big evolutionary questions, to find new technological and clinical research applications, and to engage the public with evolutionary research.

Wills explains: “The scientists at the Milner Centre are world-leading researchers into evolution and they are at the forefront of translating evolutionary science directly into human and environmental benefits."

“As understanding evolution is key to the Life Sciences, at the Centre we also research the best ways to teach evolution in schools and to convey the latest findings to the wider public.”

Stepping Into the Future

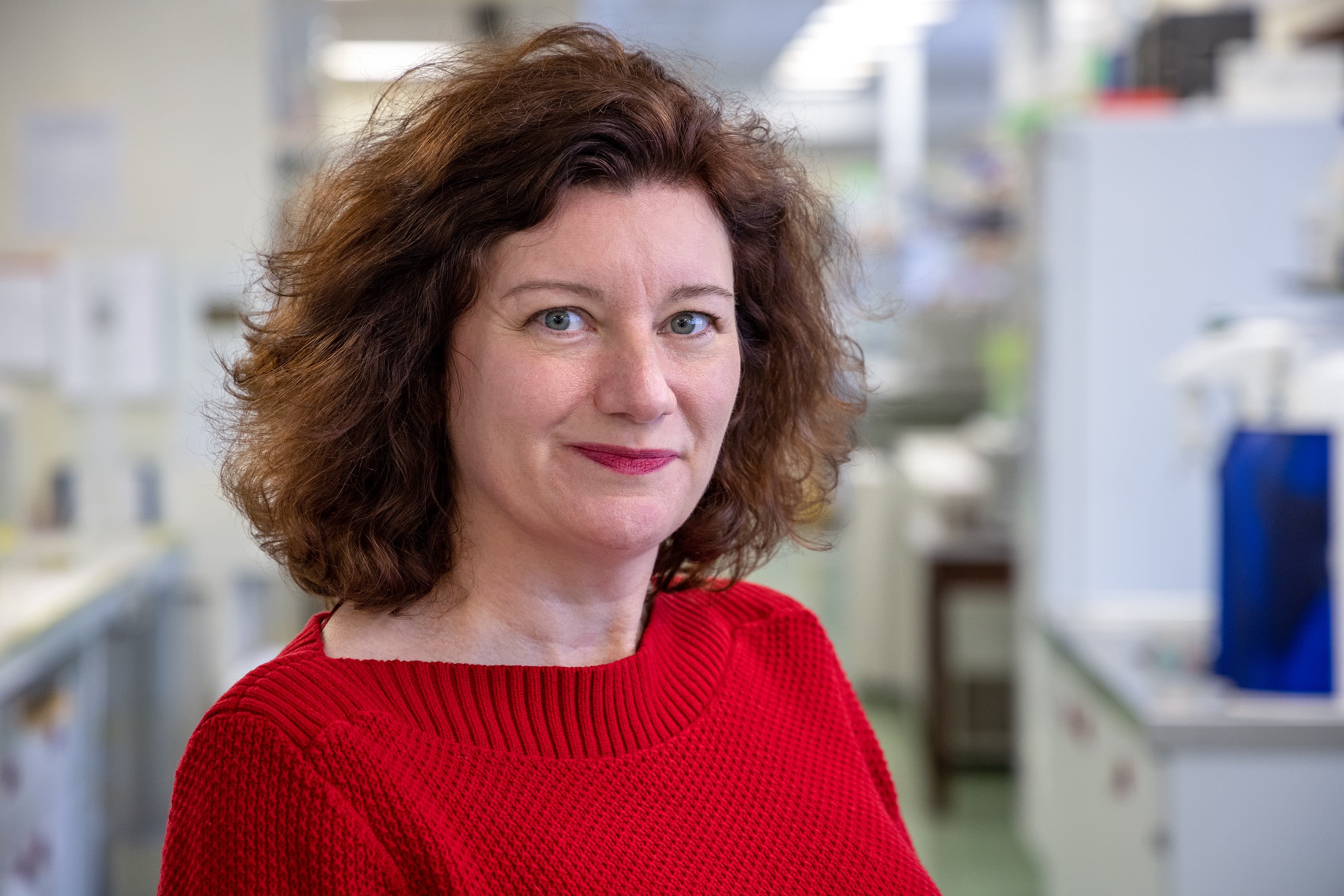

The Centre’s culture of research excellence and public engagement on evolutionary science is something that will be brought to the fore with the appointment of the next Director - scientist, presenter and author Professor Turi King.

Professor King says: “I want the Milner Centre to be known nationally and internationally for its research expertise around evolution and the teaching of evolution.

“I envision us linking up with similar groups and institutions across the UK and globally to work on joint projects, host conferences and create opportunities for students and staff to do residencies.

“I also want to grow our outreach through online, broadcast and social media, podcast and video content, alongside in-person events such as public lectures and working with schools.

Professor King applies her genetics expertise to the fields of forensics, history and archaeology, and is perhaps best known for her work leading the genetic identification of the remains of King Richard III in 2012.

She is no stranger to communicating science to a wide range of people, giving public lectures, writing popular science books and featuring in a number of TV series on the BBC, Sky History and Curiosity Stream.

Professor King says: "What is also really pleasing is that my vision aligns with that of Dr Jonathan Milner for the Centre: I feel like I’m taking his baby into the next stage of its life.”

The next stage of development for the Milner Centre for Evolution builds on an already outstanding foundation.

Tackling global challenges

Researchers at the Centre are using the latest genomic sequencing technologies to track the evolution of bacterial infections, and devise ways to prevent their escalation into pandemics, cracking the evolutionary mechanisms by which they develop resistance to antibiotics.

“Members of the Centre are developing new tools to monitor public health through the wastewater system, by identifying markers of disease enabling us to track outbreaks in near real-time, as well as detecting the spread of anti-microbial resistance,” says Professor Wills.

Evolutionary science is also being used to understand how human genes have evolved and interact in our first few days of embryonic development, offering insights into genetic diseases, infertility, and miscarriage.

Other research at the Centre investigates the evolutionary history of parasites and fungi that cause human disease, understanding how they interact with their host and paving the way for new treatments.

On a broader scale, researchers at the Milner Centre for Evolution are assessing the effects of climate change on global bird populations, and exploring how this affects their migration routes and risks of predation.

A better understanding of how animal and plant groups have responded to environmental change and mass extinctions in deep time also helps us to predict the effects of the current biodiversity crisis.

Researchers from the Milner Centre for Evolution are also using their research to help preserve biodiversity directly. A wonderful example of this is the Centre’s support of a non-profit conservation project in Cape Verde that promotes eco-tourism and engages children with endangered wildlife on their doorstep. Together, they are protecting unique shorebird populations and bringing turtles back from the brink.

Closer to home, researchers are working with local volunteers to collect survey data on bats living in the UK, using the data to better understand the effects of human noise and light pollution on their activity and then feeding this information into the local governmental planning processes for new housing developments.

Curiosity-driven research

Complementary to the applied research, researchers at the Milner Centre for Evolution also ask fundamental blue-sky questions at all scales, from molecules to genomes, organisms, populations, species and clades.

Professor Wills says: “At our heart, all of our research is driven by curiosity. We pursue the most interesting evolutionary questions because they are engaging and challenging, and not because we believe that they have translational value from the outset.”

The Evolutionary Knowledge Paradox

Professor Wills says: “The study of evolution and the study of biodiversity are inextricably linked, but herein lies an unfortunate paradox.

“On one hand, public awareness of the dangers of climate-change-induced biodiversity loss has never been greater. On the other hand, the teaching of biodiversity – both in universities and especially in schools – has been declining in recent decades.

“It seems as though an emphasis on human biology, biomedical sciences and reductionism - vital though they are – may have come at the expense of learning the grand structure of the Evolutionary Tree of Life.

“I believe this is a worrying development because evolutionary perspectives can offer the best way to set conservation priorities and they are vital for the holistic “one health” approaches needed to solve our most pressing and complex global challenges.

Education and engagement

A core aim of the Milner Centre for Evolution is to increase the general interest in and understanding of evolution through public engagement and improved education in schools.

Prof Wills says: “There are many misconceptions about how evolution works. For example, people often use language implying that organisms strive towards a goal, such as giraffes evolving long necks so that they can reach the highest leaves. Thinking in this way is intuitive and goes back to Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in the 18th Century. However, Darwin showed that it’s entirely wrong. Giraffes have long necks because they inherited them from their most reproductively successful ancestors, who had no eye to the future. Unfortunately, these superficially similar Lamarckian ideas are extremely difficult to replace with the correct Darwinian ones. This is why careful teaching of evolutionary concepts from a young age is vital.

Members of the Centre have done research into how to improve the teaching of evolution in schools, using rigorous randomised trials of different teaching methods and curriculum design. They found that simply switching the order of topics to teach genetics to children before they learned about evolution significantly improved their knowledge and understanding of the topic.

In partnership with the Genetics Society, researchers at the Centre have also investigated the reasons why some people distrust science, and how best to rebuild that confidence and fight misinformation.

Prof Wills says: “Having established the Centre, our next step is to broaden our impact by increasing our visibility and reach, and we will do this by continuing to work closely with the Evolution Education Trust, the grant-making charity chaired by our founding patron, Dr. Jonathan Milner.

“All Milner Centre members have their own active research programmes and a strong investment in undergraduate and postgraduate teaching – activities that we strongly believe are complementary and powerfully synergistic.

“We are planning to increase our support for schools, educationalists and the wider public. Our free online evolution course (MOOC) – aimed at all those teaching evolution – was a particular success. We plan to scale our impact with summer residential courses for school teachers and policymakers, where we can explore the latest findings in both our science and evolution education.”

PhD students at the Centre also communicate their research to others as part of their studies, whether it’s visiting local schools, talking to the public at Bath Festival of Nature, or making videos for YouTube.

As the Milner Centre for Evolution steps into its next stage of development under the leadership of Professor Turi King, expect to see an increased emphasis on outreach and school engagement as the Centre seeks to not only advance fundamental evolutionary research and its application, but to also measurably reduce the impact of the evolutionary knowledge paradox.

This content was paid for and created by The University of Bath. The editorial staff of The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.