Improving Diabetes Treatment with a Point-of-Care Device

A light way to improve diabetes care

Over 60 per cent of amputations above the ankle and more than 80 per cent of all foot amputations are associated with diabetes in Australia and world-wide, highlighting the need for a new intervention.

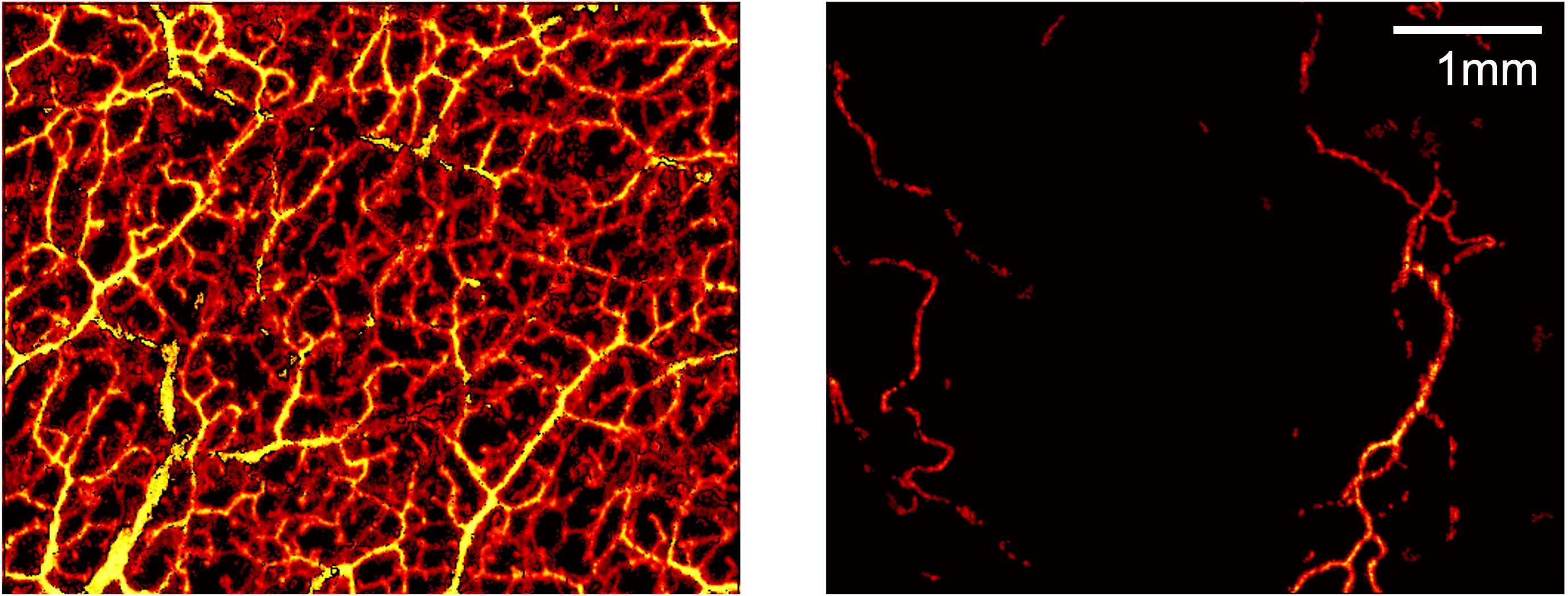

“Many of these amputations arise from diabetes-related foot ulcers that can’t heal,” said University of Adelaide Professor Robert McLaughlin, School of Biomedicine. “Your body is covered with a web of tiny blood vessels just below the surface, bringing oxygen and nutrients to the skin. These vessels are critical for keeping the skin healthy, and for healing wounds. But in diabetes, the vessels can stop working.”

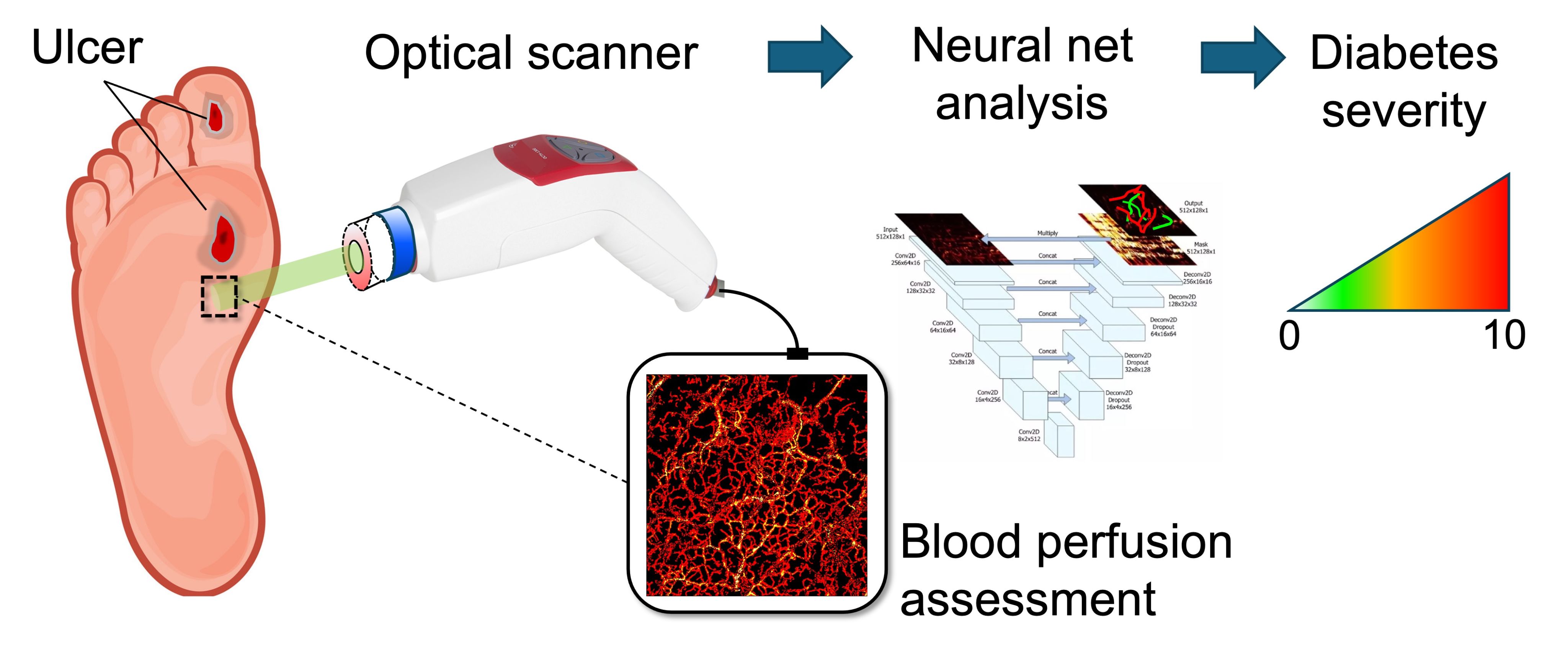

Professor McLaughlin has been working with Professor Danny Green from the University of Western Australia to change this. “One of the questions clinicians have to answer in these situations is what is the right treatment,” said Professor McLaughlin. “It can be hard to know the best treatment for a foot ulcer – will it heal by itself, do they need medication, or surgery to open up some of the large blood vessels. If we can help guide the clinicians, then the patient can heal faster, and we may be able to avoid amputation."

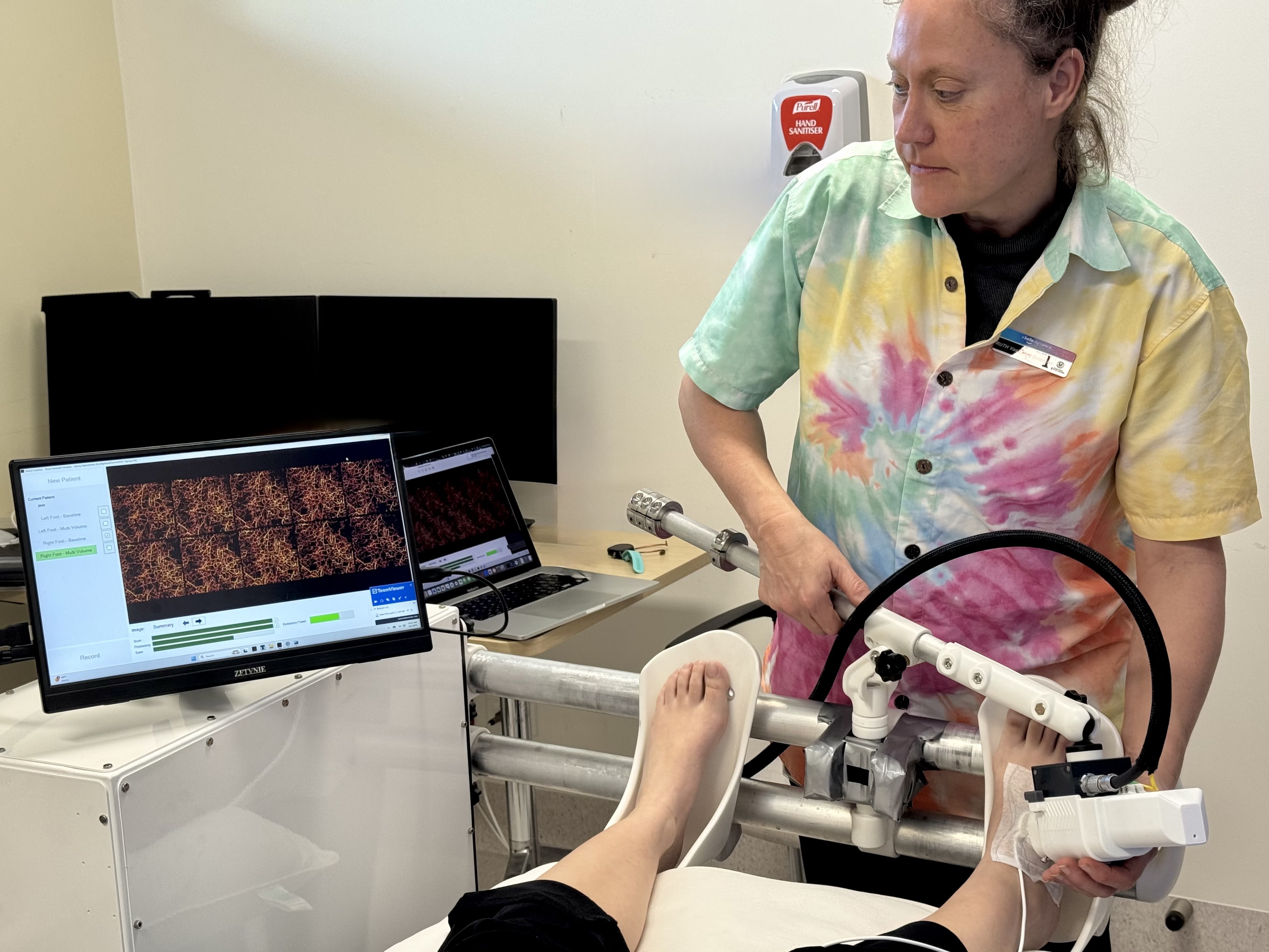

Their team has developed a new type of scanner that can see these tiny blood vessels.

Based on a technology often used in ophthalmology and cardiology called optical coherence tomography, they have patented tools allowing doctors to quickly scan the skin and measure the foot’s capacity for healing.

Professor Robert McLaughlin

Professor Robert McLaughlin

Over the past 10 years, Professors McLaughlin and Green have developed new techniques to translate it to scanning the skin. “We’ve just started our first trial at the Royal Adelaide Hospital,” said Professor McLaughlin. “What we’ve seen is that there’s a clear difference between the vessels in healthy feet, and patients with late-stage diabetes. It’s like night and day.”

The trial is being led by Professor Robert Fitridge, Professor of Vascular Surgery with the University of Adelaide and co-lead of the multi-disciplinary foot service at the Central Adelaide Local Health Network.

“Adelaide is a great place to do this type of research," said Professor McLaughlin. "We have engineers and physiologists working alongside each other, and Professor Fitridge’s team at the hospital is helping us to understand what happens when the technology meets the real world.”

One in 10 adults worldwide has diabetes, resulting in more than $5 billion annually in productivity in Australia alone. “So much time and effort goes into the health system for the treatment of diabetes related conditions. If our scanner can help us find the best treatment for a patient, then we can ease some of the burden,” said Professor McLaughlin.

The team has already mapped a path to commercialise their technology. As diabetes becomes more common, they estimate a potential market size of $1 billion for their scanner. “We want our technology to improve lives, and that will only happen when hospitals can buy the scanner so doctors can use it to find the best treatment for their patients,” said Professor McLaughlin. "We believe we have something valuable to give them. What I love about this project is that it has cool science doing amazing things with optics, it’s solving a real problem for patients, and we can see how this technology will make the leap from our lab into the commercial world. It’s science that can make a difference.”

"We believe we have something valuable to give them. What I love about this project is that it has cool science doing amazing things with optics, it’s solving a real problem for patients, and we can see how this technology will make the leap from our lab into the commercial world. It’s science that can make a difference.”

Prevention is key

At the University of South Australia's Regenerative Medicine Laboratory, Professor Allison Cowin is exploring ways to heal wounds and even recognize potential risks before they happen. It's an area Professor Cowin is passionate about, and she is hopeful change is on the horizon. In 2021, she was part of a team awarded research funding for the Australian Centre for Accelerating Diabetes Innovations (ACADI) project.

Professor Cowin and her team focus on personalized care strategies for wound care for patients with diabetic foot ulcers, investigating the biological make up of wounds to identify specific proteins present. "The idea is to develop new ways to treat diabetic wounds," she said. "We are working to create a test that would reveal biomarkers within the blood of those who are at risk of developing diabetic foot ulcers. Imagine if we could do this test as we do a simple blood prick test to look at blood sugars. This would allow us to see any risks early on and help people manage their diabetes wound risk better -- we're not there yet, but we're working on it."

Last year, type 1 diabetes was responsible for almost 20,000 years of healthy life lost in Australia and 128,000 years of health life lost for people with type 2 diabetes. "Ultimately, our research aims to improve the lives of those affected by diabetes-related foot ulcers by developing more targeted and effective treatment strategies," Professor Cowin said. "Part of this too is working with the community and raising awareness of diabetes. As a chronic condition, people do get stuck in the thought that those with diabetes deserve it, that it's a result of a lifestyle choice for people with type 2 diabetes particularly, but there are a number of causes and reasons. In 10 years' time, we will hopefully have a new cell based dressing for wounds to help them heal and a biomarker platform to identify those people who are at risks of serious wounds and ulcers."

"This would allow us to see any risks early on and help people manage their diabetes wound risk better -- we're not there yet, but we're working on it."

This content was paid for and created by the University of Adelaide. The editorial staff of The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.