Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Responds to COVID-19

With the COVID-19 outbreak, institutions of higher education are facing unprecedented challenges. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin was among those that rapidly took steps to protect personnel who remained on campus. It also developed the means to deliver its summer semester through online methods. And medical researchers there have worked on combating the virus with additional funding.

Research contributions have been coming from many quarters. Very quickly, a renowned researcher at Humboldt, Dirk Brockmann, with colleagues at the Germany’s central scientific institution for biomedicine, the Robert Koch Institute, developed a model for calculating the probability of an infected passenger from Wuhan, the Chinese state where the pandemic began, arriving at any airport in the world. To do that, the researchers used the Worldwide Air Transport Network (WAN), which connects 4,000 airports with more than 25,000 direct connections.

That allowed them to model the movement of people who might be infected, and that showed why and how the risks of infection are unevenly distributed throughout the world. It also has enabled Brockmann and his colleagues to design two coronavirus mobile-phone apps.

The freely downloadable smart-watch and fitness-tracker apps have two key functions. One is to gather data about users’ health and to send out alerts about possible contact with infected app users. The data is not centrally stored, and the voluntary users are guaranteed anonymity. That advances the apps’ second function: to encourage users to donate their data for analysis by Brockmann and other researchers.

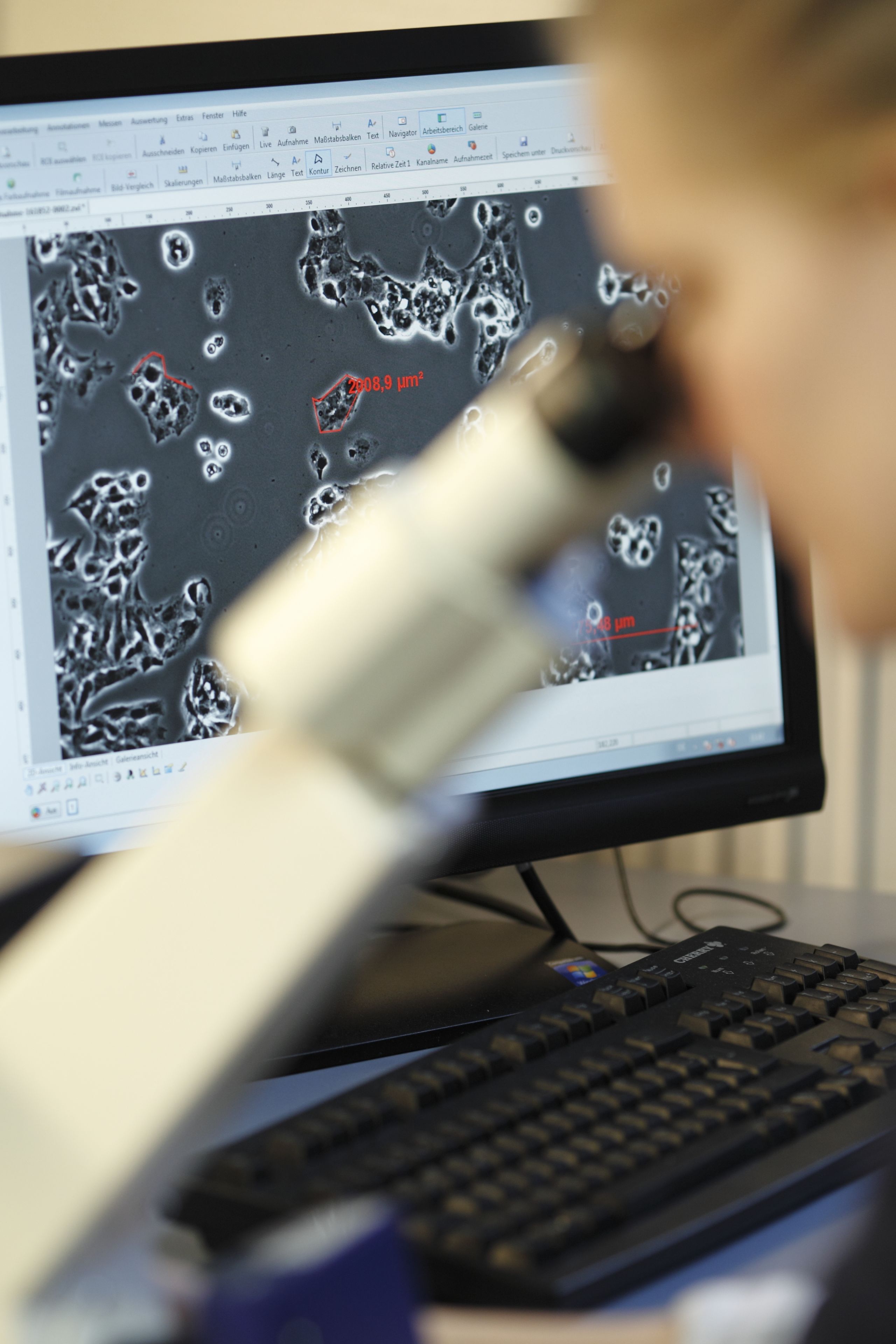

Other Humboldt scientists are working to find treatments for COVID-19, or at least approaches that may lead to treatments. Humboldt researchers together with colleagues in varied fields at two other Berlin universities and the city’s Charité hospital, all members of the Berlin University Alliance, are using €1.8-million in Alliance funding to develop comprehensive and novel strategies.

The approaches may include synthesizing and testing antiviral therapies, using human-tissue models as well as animal and surrogate models, developing long-lasting vaccines, studying the course of the disease, and modeling the spread and consequences of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic — the last of those, as Brockmann’s apps are doing.

Of course, organizing research responses to complex health phenomena is itself very complex. There, says Christian Hackenberger, a professor of chemical biology at Humboldt and the independent Leibniz Institute for Molecular Pharmacology, he and his colleagues at Alliance institutions are well set up to respond.

“The really strong aspect of this consortium is that we can gather expertise from different areas, which is also one of the strengths of the German system. Our whole funding system is based on a lot of collaborative initiatives.”

In addition, his and colleagues’ work on such challenges as fighting influenza and other infections: “We did not have to invent or develop this network from scratch when the COVID outbreak was happening.”

That work developed ways to share various researchers’ skills and findings, agrees his Humboldt colleague, Andreas Herrmann, a professor of biology who specializes in molecular biophysics. For example, in work on the influenza virus, “our goal was to attack the cellular receptor in the respiratory tract, and the new coronavirus is also a respiratory virus.”

That makes him guardedly optimistic that the group will be able to contribute soon to the search for treatments of the new virus.

One possible approach, Hackenberger says, may be to synthesize molecules that will bind to the Covid-19 virus, and neutralize it.

While it is too early to tell which sorts of approaches will work, there is no doubt that “it comes down to being stronger in a team.”

In their approach to suppressing seasonal influenza, published in Nature Nanotechnology, the Humboldt researchers and their Alliance colleagues have created molecules that perfectly fit the binding sites of influenza viruses and “stifle” them, making them incapable of infecting lung cells.

That Humboldt’s response has included contributions in research and innovation is in keeping with its traditions. Twenty-nine Nobel Laureates have pursued their research there, including Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Robert Koch, and Fritz Haber. And Humboldt was, at its inception in the early 19th century, a blueprint for modern research universities around the world. The vision of its founder, Wilhelm von Humboldt, was to create an institution built around research where teaching was integral to that emphasis. In 1954 Max Born, a pioneer of quantum mechanics, won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his revolutionary conception of natural phenomena.

In addition to its research response to Covid-19, Humboldt has mounted a rapid and active operations plan. In early February, just as governments in the West became aware of the likely threat of the mounting pandemic, Humboldt introduced precautionary measures and set up a dedicated Coronavirus task force to coordinate their implementation.

Humboldt began developing, in March, ways to recommence classes and soon had made plans to do so. On April 3, the state government directed higher-education institutions in Berlin to start delivering summer-semester lectures digitally from April 20 — and to do so with “flexibility, consideration, and reliability.”

Berlin state’s Governing Mayor and Senator for Education, Michael Müller, and state Secretary for Higher Education and Research, Steffen Krach, announced that state, denominational, and private universities had all agreed to that approach. The higher-education agency provided €10-million immediately for innovation within the VirtualCampusBerlin as well as funding to provide more than 1,000 instructors around Berlin with access to digital-teaching training resources at the Berlin Centre for Higher Education.

The president of Humboldt-Universität, Sabine Kunst, announced that the university had already been working towards getting the summer semester started on time, and that did occur on time. She said she was heartened by how supportive state and higher-education authorities were of that goal.

“I trust in the great creativity of all those who are developing the new digital offerings in cooperation with the students and I am certain that a lot of new and exciting things will emerge.”

She cautioned that online delivery could not be perfect, and sometimes would be tentative, “because the translation of previous courses into digital formats takes time and experience. On the other hand, this is a great opportunity to restructure and create models for the future of teaching.”

The university’s Computer and Media Service staff — engineers and other staff members working in education science, accessibility services, and other fields — have been working on those innovations, she said. But so too have faculty and staff members across the whole institution.

A striking indication of the success of the approach is that 85 percent of courses are successfully being conducted online.

This has been taking place even while Humboldt personnel have been working with liberalized conditions that allow them to care for their families.

To increase the safety of students and personnel within and beyond classrooms, Humboldt’s Department of Chemistry rapidly deployed to produce large quantities of disinfectant. That supply of hundreds of liters per day has been enough for campus staff to disinfect the campus thoroughly, and for the university to donate to the nearby Charité hospital whatever it needs to top up its daily requirements.

The Humboldt chemists were also able to produce disinfectants for surface cleaning and personal hygiene to specifications provided by the World Health Organisation. The ingredients include ethyl alcohol, glycerine, and ethanol, the last of which is in short supply, globally. Fortunately, Dow Chemicals, which had donated a metric ton of finished disinfectant to the Charité hospital, also gave Humboldt-Universität ingredients to make more.

In a pandemic crisis, some approaches potentially offer global solutions, while some measures are necessarily just local. Humboldt-Universität is working hard across that spectrum.