How to build a pandemic response plan:

A data oriented approach to campus reopening

Until recently, college leaders faced a diverse array of worries, from finances and retention to greater public scrutiny. This year, their concerns are coalescing around a single issue: Covid-19. How can their institutions reopen safely? What form should that reopening take and how can the variety of stakeholders that comprise their campus be reassured? Also, how can they model and adapt quickly to new information?

The challenges presented by fall term 2020 are unprecedented, tasking administrators with a wide set of issues that require thoughtful decision making often without the benefit of historical precedent. Major decisions include deciding what proportion of classes should be held online, how many can be safely be accommodated in student housing, how to support stressed faculty, and what the college experience in the era of Covid-19 ought to look like. All need to be evaluated, decided, communicated and implemented in a matter of weeks.

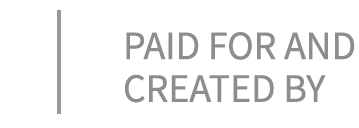

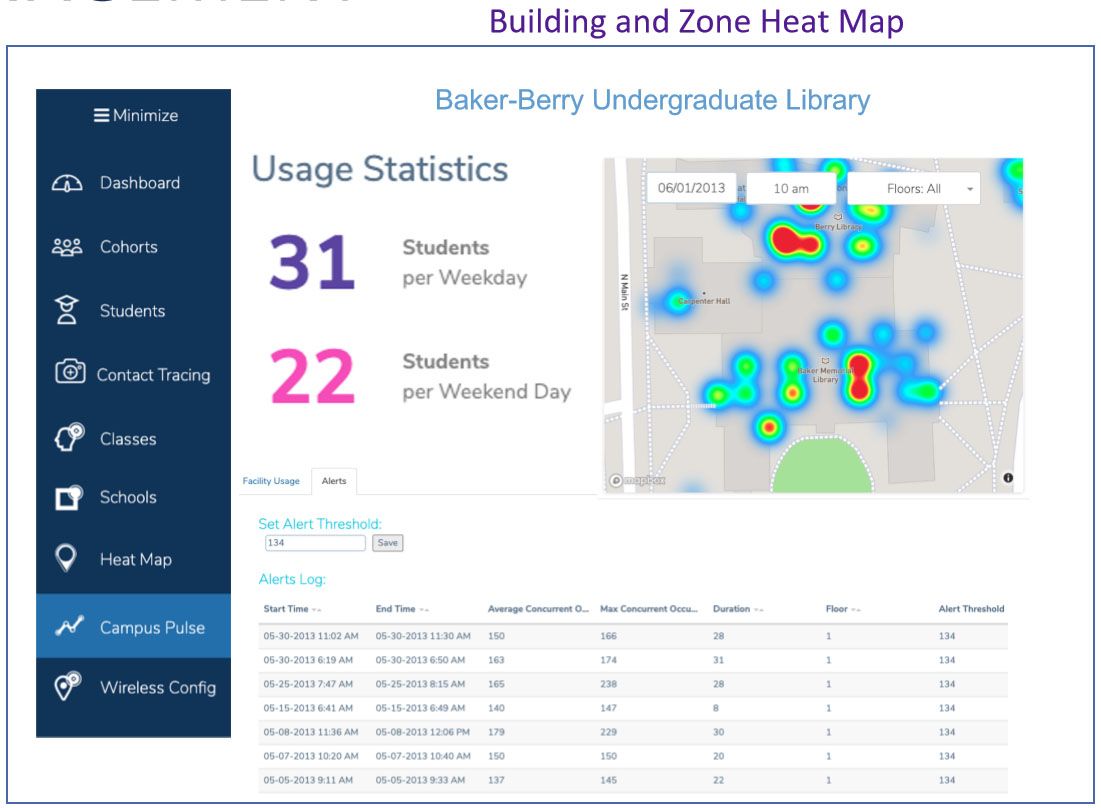

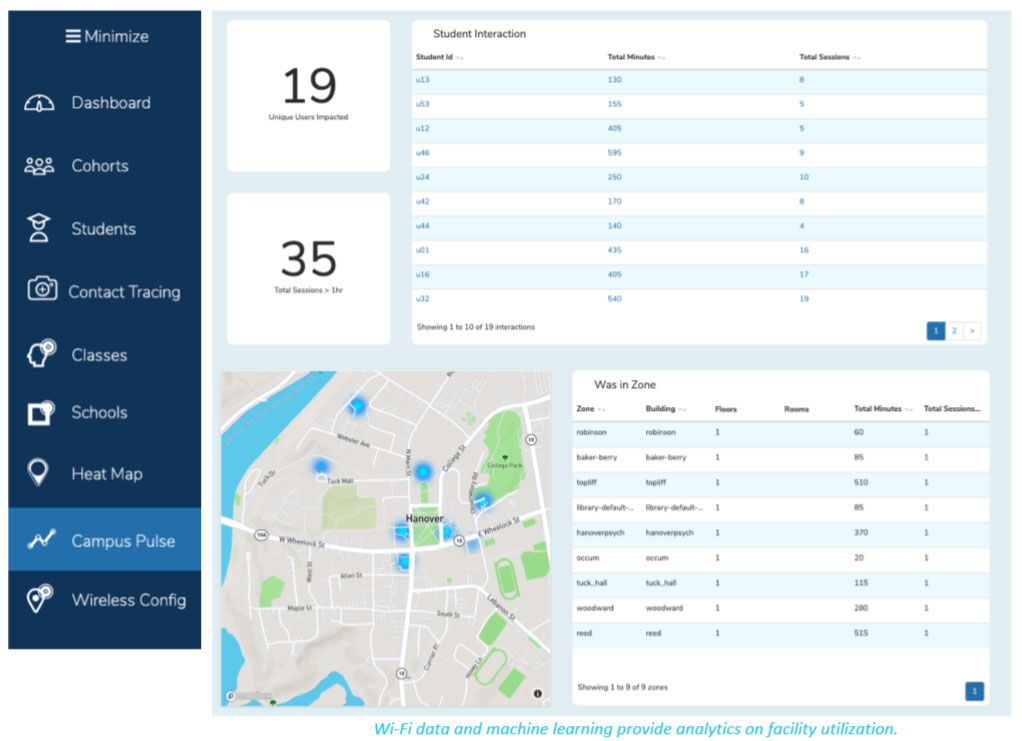

Some leaders, moreover, are finding that data mining and machine learning technologies may help in both their decision making and implementation. Before the pandemic’s arrival, certain colleges had decided to adopt these innovative technologies, tools widely used in other sectors to measure behavior and target communication based on wireless connectivity of various devices. In higher education, these tools offer insight into class attendance and participation in extracurricular activities. The pandemic has made this data both informative and actionable: It can show administrators how many students are on campus, what facilities they are using, and whether they are gathering in numbers in excess of their physical distancing protocols.

Higher education has traditionally been slow to change, but industry leaders now say the pandemic could propel it into the future.

More connected than ever before, but how are students connecting with campus?

Degree Analytics offers a technology-based platform which allows college leaders to observe student engagement with campus. The company, serving 200,000 students in twenty institutions, lets college leaders view depersonalized patterns of wireless connectivity across the campus. Aaron Benz, its founder and CEO, is quick to note that the technology acts as a system to inform decisions; it doesn’t intervene in how they are made. “It gives you the opportunity to shine a light on the breadth of campus engagements and their impact on student success and satisfaction, and now more importantly than ever, student health and safety,” he says.

One such institution is Colorado Mesa University, which began using Degree Analytics’ technology in 2018. Situated near the majestic outdoor vistas of western Colorado, the university has grown by more than 50 percent over the past two decades, evolving from a largely commuter college to one in which a quarter of students live on campus. Many are the first in their families to go to college.

Student surveys and card-swipe data provided a partial picture of student activity but CMU’s President, Tim Foster, wanted to get a better sense of how it could support them, Jeremy Brown, Vice President of Information Technology at CMU, explains. “I don’t think we knew enough about our student population and what services they needed—whether it was commuter students or those who live on campus — to even know where to begin,” Brown says. “Degree Analytics’ data allowed us to have a broad view of what was going on for different student cohorts.”

Academics and leaders in higher education increasingly acknowledge that attendance is a key indicator for success, particularly for first-generation students. In recent years, administrators have begun asking professors to take attendance in class or even make attendance mandatory. Wireless attendance checking takes a different approach. Brown describes a young woman who had been high achieving in high school and came to CMU with good grades and solid test scores. Living in a nearby community to campus, she hardly presented cause for concern — until the data revealed she wasn’t attending class and had not left her dorm in weeks except to eat. With these insights, student services were engaged and provided the opportunity to support the student early in her campus journey.

Perhaps, ironically, technology can give institutions a more human touch. Students who are not attending class might be contacted by college staff to see how they are doing, Brown explains. While professors and resident assistants (RAs) typically check on students partway through a semester, wireless data can highlight problems at an earlier stage. “By far the best outcomes of this advanced data usage has been how quickly we can now identify students that may not be connecting with other students and campus services and activities,” Brown observes, “and therefore are at a higher risk of not staying in school.”

By showing how facilities are used, the data can also indicate where investment is needed. At CMU, one student had asked for a 24/7 study area to be enlarged, but wireless data showed enough workstations in place to meet demand. In contrast, data revealed a health and exercise facility was very busy, even oversubscribed, so the university expanded access by adding a fitness room to a residence hall to encourage healthy living. An example of how institutions can use evidence over intuition in terms of resource planning.

“Even before the pandemic there were already a lot of competing interest for limited financial resources,” Brown says. “So to make the best decisions on how you use funding to support students and provide services is key.”

Degree Analytics can use your current network infrastructure to increase visibility into student presence on campus, providing insight into who is on campus now and keeps you informed as you plan for students’ return.

Degree Analytics can use your current network infrastructure to increase visibility into student presence on campus, providing insight into who is on campus now and keeps you informed as you plan for students’ return.

Covid-19: Managing the chaos

With the arrival of Covid-19 in March, Brown and his colleagues at CMU immediately understood that wireless data would play a role in their response. Administrators could use technology to verify the number of students on campus and plan for meal preparation and staffing. If students left without filling out the right forms, CMU could pinpoint when they left campus and refund their housing fees if appropriate. The closure happened over spring break as teaching went fully online, Brown explains. “Many students did not return until later to pick up their belongings. Students that needed to stay due to family or housing situations required campus services. With the data at hand we were able to make informed decisions and better support all members of our university community.”

Campus Pulse guards the health and safety of the on-campus community by providing timely and relevant insights to campus visibility.

Campus Pulse guards the health and safety of the on-campus community by providing timely and relevant insights to campus visibility.

Degree Analytics’ Chairman and Chief Academic Officer, David Palumbo, previously a tenured professor and administrator in higher education, says that at the start of the pandemic the company developed a hierarchy of students’ needs. “One of the things we started to ask ourselves as early as March is: Are students going to come back to higher education? If so, when will they return and where will they return to? And most importantly, how are they going to make their decisions? We really believe that the base layer driving students’ decisions —and therefore their actions — is safety. ‘Am I safe?’ and ‘Do I feel safe?’ are two really important questions likely to drive all students’ initial decisions to return to campus.”

These questions have also surfaced at Framingham State University in Massachusetts, which serves a largely local population alongside a small number of out-of-state and international students. As the fall semester looms, the college’s president, Dr. Javier Cevallos, is pondering how to address them and considering adopting innovative technologies to help model and manage campus reopening. At the forefront of his mind is the students’ physical wellbeing. “Obviously the health and safety of everyone worries me. We’re making decisions about opening an institution that has an impact on the health and wellbeing of the entire Framingham State community.”

Cevallos says he is concerned about students’ mental health, too. For freshmen in particular, college is not just an academic but a social experience, a pivotal moment in a young person’s life. The uncertainty and constraints imposed by the pandemic place an extra burden on vulnerable students, Cevallos notes. “I think mental health and mental well-being are going to be really important and we need to pay attention to it.”

A privacy trade-off

College leaders say it is vital to be transparent about informing students they are using the data mining technology, and to give students the option to opt out if they wish. But some think this type of data privacy is not a major concern for this generation. “There is a big difference in today’s students compared to when I was a student and even compared to ten years ago,” Cevallos says. “The concept of privacy and personal security has changed. I think that students today feel that security and safety is much more important than data privacy.”

Jeremy Brown of CMU agrees. Although a small number have chosen to opt out at CMU — “and that’s fine,” he says — the majority understand the university’s goal is to help them succeed. “I think for the most part students like a little bit of — maybe it’s more home-like, where there’s that nudge that says, ‘Hey, we care.’ I don’t think they look at it in a negative fashion.”

When health and safety are compromised, how do you quickly contact those affected directly and indirectly? Campus Pulse helps trace contaminated locations and support the shift to a ‘public health mindset.

When health and safety are compromised, how do you quickly contact those affected directly and indirectly? Campus Pulse helps trace contaminated locations and support the shift to a ‘public health mindset.

For Riley Campbell, a 20-year-old student at The University of Texas at Austin, data privacy and its relationship to tracking technology are topics she and her friends discuss. The architectural engineering student currently working as an intern at Degree Analytics says her peers don’t always agree. But with companies already using data for nebulous purposes, she thinks deploying it to counteract Covid-19 should not pose a problem. Some people will always worry more than others about privacy, Campbell adds. “In the case of Covid contact tracing, it’s for a higher purpose beyond yourself, so people are more willing to participate in it because it’s helping other people and not just them,” she says.

Unprecedented insight

As colleges plan for whatever they may face in the fall, knowing how many students are on campus and exactly where they are will offer an invaluable bird’s-eye view, helping to inform a broader Covid-19 response. Colleges may need to test faculty and students, conduct contact tracing when someone falls ill, reconfigure or sanitize classrooms and monitor facility usage. In some schools, students have been voicing worries about wait-times to access facilities and additional obstacles for those with disabilities. To preempt such concerns, CMU is considering a traffic light system that would allow students to avoid one dining hall if it currently exceeds density limits and go elsewhere. “We think it will help them plan their day,” says Jeremy Brown.

These technologies may help catapult higher ed. into the future, enabling better support for students and allowing college leaders to navigate the pandemic and the future. This tumultuous and challenging time for institutions could in that sense have a silver lining.

As Jeremy Brown puts it, “Degree Analytics has allowed us to look at our student population at scale.”

He adds, “The data was helpful to CMU even before the pandemic. We need to do everything we can to help the students engage at our university, and this is one tool that we can use to help us work towards that.”