How a student center can improve long-term outcomes

University of Florida’s Center for Undergraduate Research teaches students about scholarship, studies and professionalism

Phong Truong’s research has already brought him from Florida to Maryland to Uganda and now Switzerland, where he is currently enrolled in a Master’s program at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva.

But it was early on, as an undergrad at the University of Florida (UF) that the young scholar’s interest in research was first sparked. Staff at UF’s Center for Undergraduate Research (CUR) encouraged Truong, then majoring in microbiology and cell science, to apply for a stipend for emerging scholars, which supported his work at a lab studying Alzheimer’s disease. Then he received an undergraduate research scholarship; then another UF award, to spend a summer in a lab in Uganda.

The Center showed how many opportunities there are for undergraduates, says Truong. His time in the Alzheimer’s lab gave him the opportunity to work alongside leading scientists and doctoral students, and taught him about rigor, peer review and reproducibility.

“It opened my mind,” he says. “The research skills, in terms of thinking clearly and writing well, have been tremendously helpful. In my studies and coursework, in class discussion, in everyday life—I get to apply those skills and continue to practice and challenge myself.”

How to fail, succeed—and thrive

For several decades, studies have shown that taking part in research as an undergrad correlates with positive outcomes for students in terms of both graduate school placement and employment. Administrators at UF have honed a particularly successful program, built on encouraging students’ autonomy and independence.

The Center offers an array of scholarships, travel awards and funding grants. It connects students with their peers and with faculty across humanities, social science and the natural and applied sciences—opportunities that are open both to students pursuing degrees in person and to those studying online. When participating in research projects, students can decide not to take credits, so that they can pursue their interests without accruing college fees, a policy that broadens the program’s appeal.

Anne Donnelly, who created CUR in 2010, said it was founded in part to capitalize on the University’s rising profile as a research institution. Students are not handed projects, but encouraged to pursue areas that interest them. “This is kind of my philosophy. I'm not here to match them,” she says. “Every faculty [member] on campus is doing research... We give the students the skills to identify who they might want to work with and teach them how to professionally make the initial contact.”

The program helps some students crystalize their wish to embark on a research career; it helps others figure out that their path lies in a different direction. All students who engage in the Center’s activities emerge with a richer set of skills that will help them with when graduate, Donnelly notes.

“They learn problem solving. They learn how to look at data and analyze it. They learn how to fail. They learn how to persevere. So even if they're going to be a doctor or a lawyer or an investment banker or a high school teacher— there are no skills there that won't help them,” she explains.

Anne Donnelly, Ph.D., director of UF’s Center for Undergraduate Research (CUR)

Anne Donnelly, Ph.D., director of UF’s Center for Undergraduate Research (CUR)

Advice for administrators

Obtain leadership buy-in. The Center for Undergrad Research (CUR) is part of the office of the Associate Provost for Undergraduate Affairs. Not only does this ensure institutional and financial support, it also means the program is not identified with a particular department or college. “It makes it easy for us to serve students in all disciplines, all colleges, all departments,” Donnelly says.

Choose an easy-to-access, high-profile space. CUR is located in a building in the middle of campus, accessible to students 24/7. “This makes all the difference in terms of students finding you,” she says.

Make it inclusive. Some student research centers start out as honors programs but CUR serves all students.

Be appropriately staffed. In addition to its army of volunteers, CUR has three full-time staff and eight part-time student assistants. Having two or three people working full-time on the Center helped get it up and running, Donnelly notes. The fact that Donnelly holds a PhD facilitated the process by making conversations with faculty easier.

Involve students right away. This is key—not only involving the young people but also trusting them, she stresses. At CUR, students are “totally intertwined with management decisions.”

Connect with colleagues. Donnelly recommends having a more experienced colleague “on speed dial” to help with tricky questions. The National Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR) is a good source of advice and support.

Student-led

A key aspect of how the Center instills these skills is by giving responsibility to students. It has a highly active and self-directed advisory Board of Students, CURBS. And alongside regular activities, students help organize four landmark events during the year, which attract hundreds of participants: a fall undergraduate research expo; undergrad research symposia in spring and fall; and a statewide undergrad research leadership summit.

Dr. Muna Oli, an anesthesiology specialist who completed her undergraduate studies at UF in 2015, credits CUR with facilitating research opportunities within and beyond UF. Brendan Wernisch, the current Executive Director of CURBS, says his experience with the board was instrumental in his acceptance into selective graduate programs.

Dr. Muna Oli, an anesthesiology specialist who completed her undergraduate studies at UF in 2015, credits CUR with facilitating research opportunities within and beyond UF. Brendan Wernisch, the current Executive Director of CURBS, says his experience with the board was instrumental in his acceptance into selective graduate programs.

Donnelly, who manages the center with the support of two full-time staff and eight student assistants, says that student involvement is key. Her small team is supported by a band of student helpers, who donate about 2000 hours a year to the organization, connecting with other students and spreading the word about the group. “Students would rather hear from other students,” she says.

This also applies to broader decision making. “You not only have to follow students, but you have to give them real work and trust them and incorporate them into the management decisions of the organization,” Donnelly says.

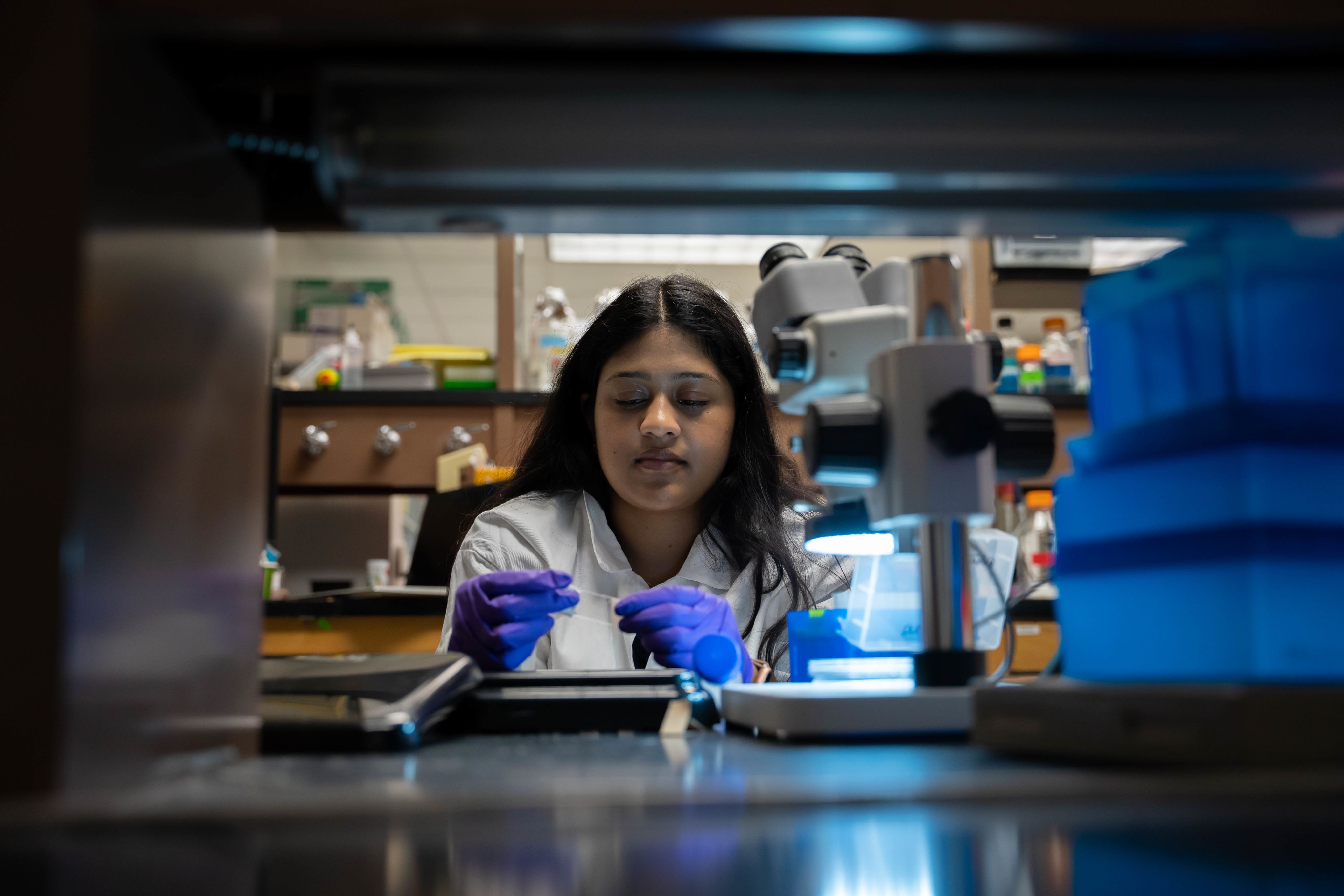

Pravalika Manda, a senior majoring in microbiology and cell science, is Director of Special Projects for CURBS. Her communication skills and professionalism have greatly improved as a result of her role, she says—“because you're talking with faculty, you're talking with students on a daily basis.” Putting on events has compelled her to become better organized and to manage her time. “It takes a lot to put on those events but—we're also students, and we're also doing research and we also have other things going on. So just trying to find the balance of how do I do all this in a timely manner, without overwhelming myself, but also making sure the event goes smoothly.”

Pravalika Manda, UF Class of 2023

Pravalika Manda, UF Class of 2023

Brendan Wernisch, a senior majoring in chemical engineering, is the current Executive Director of the student board. Wernisch, a first-generation student from a single-parent family, began research by doing what he describes as “silly little experiments” in high school. From an early age, he knew he wanted to do research, and CURBS gave shape to that wish. “I felt very inspired that people who were not much older than I was, were so mature and professional,” he says. “It was really the people on the leadership team that drew me to further involvement.”

Participants at the Florida Undergraduate Research Leadership Summit organized by UF’s Center for Undergraduate Research Board of Students (CURBS).

Participants at the Florida Undergraduate Research Leadership Summit organized by UF’s Center for Undergraduate Research Board of Students (CURBS).

Preparation for post-grad life

Presenting ideas to dozens, sometimes hundreds of people, organizing events, speaking with faculty and doing peer-to-peer outreach allows students to gain valuable experience. It enables them to polish their resumes and stand out in a crowded field. When Jamarcus Robertson, an alumnus of CURBS, was applying to grad school at the University of Chicago, he felt the interview panel was impressed by the depth of his leadership activities. Robertson had received scholarships as part of the National Science Foundation (NSF) Florida Georgia Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (FGLSAMP), the McNair Program for first-generation students, and as a first-generation student was selected for the Machen Florida Opportunity Scholar (MFOS). At CURBS he became Director of Special Projects, among other roles at the Center. At his interview, his work “really did set me apart,” he says.

The extensive peer-to-peer work informs Robertson’s approach to mentoring even now. At Chicago, he is pursuing a doctorate exploring what sea anemones can reveal about cell regeneration and wound healing. “Whenever I have a student that's coming in, I usually help them in the lab in the context of how to do experiments and how to understand things. But,” he adds, “I also try my best to help them understand that there's more out there that they can do to really take that next step.”

UF’s dedicated Center for Undergraduate Research has spurred hundreds of students to expand their horizons. For Phong Truong, it uncovered a world of problems and puzzles and the part he could play in solving them. During his three months in Uganda, where he helped to study biomarkers found in blood samples and cerebrospinal fluid to better understand how severe forms of malaria affect children, he deepened his understanding of health inequities. Truong now studies the intersections of science, politics and philosophy, and is doing a thesis on the politics of artificial intelligence ethics.

“It was very formative,” he says, “and showed me where individuals can contribute to resolving the difficult and wicked challenges in the world. There's a lot of research that we still need to do to better understand these issues and tackle them.”

This content was paid for and created by University of Florida. The editorial staff of The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.