Deepening Global Understanding of Indigenous Treaties

Indigenous issues today rightfully occupy the center, rather than the periphery of debate. International bodies recognize that the future of climate change adaptation, water conservation, and ‘clean’ energy is intimately tied to Indigenous nations, their lands and territories. Why? Because the world’s 370 million Indigenous peoples live in over 90 countries and are custodians of a very significant percentage of global diversity, including 37% of remaining natural lands worldwide and a high proportion of the transboundary river basins and aquifers that form the earth’s systems.

“Only by taking into account Indigenous knowledge, treaties, and rights can we solve our most pressing global problems”, says Joy Porter, Professor of Indigenous and Environmental History at the University of Birmingham, U.K.

Professor Porter is the Principal Investigator of the Treatied Spaces Research Group, an internationally collaborative enterprise that works across disciplines and sectors to make treaties and environmental concerns central to education, policy and public understanding. “The Treatied Spaces mission is to insert Indigenous concerns into multiple debates and areas of discussion,” she says. “This is important today as never before, because the resurgence of Indigenous governance is linked directly to the resurgence of world biodiversity, and thus to world survival. Treaties remain our most unique shared intercultural mechanism for maintaining co-operation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous nations as the unprecedented technological and social change of the twenty-first century unfolds.”

Joy Porter, Professor of Indigenous and Environmental History, University of Birmingham

Joy Porter, Professor of Indigenous and Environmental History, University of Birmingham

Awareness of the interplay between Indigenous traditions and contemporary policy has grown thanks to the work of prominent Indigenous politicians. For instance, Deb Haaland, the US Interior Secretary and first Indigenous cabinet member, has prioritized the management of Indigenous land and treaty obligations, highlighting that her agency has historically been responsible for both mining and resources and Native affairs. She commissioned a report into the 400 American schools established to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children, including members of her own family, until 1969. In July it revealed that nearly 1,000 Indigenous children died while attending government-run boarding schools. Similar findings were made in Canada in 2021. Those discoveries have spurred research aimed at uncovering the continued impacts of the residential school system. For instance, a University of Calgary project collaborates with Indigenous communities to create 3D digital models of residential schools, visually representing survivors' stories and recollections. Professor Porter's Treatied Spaces Research Group has used sound and image in collaboration with Elders from the Haudenosaunee Cayuga Nation to promote awareness of the brutal happenings at Canada’s oldest such institution, the ‘Mush-hole’ or Mohawk Residential School, at Brantford, Ontario. It was owned by the British missionary organization, The New England Company, and remained open until 1970.

Revitalizing International Diplomatic Traditions

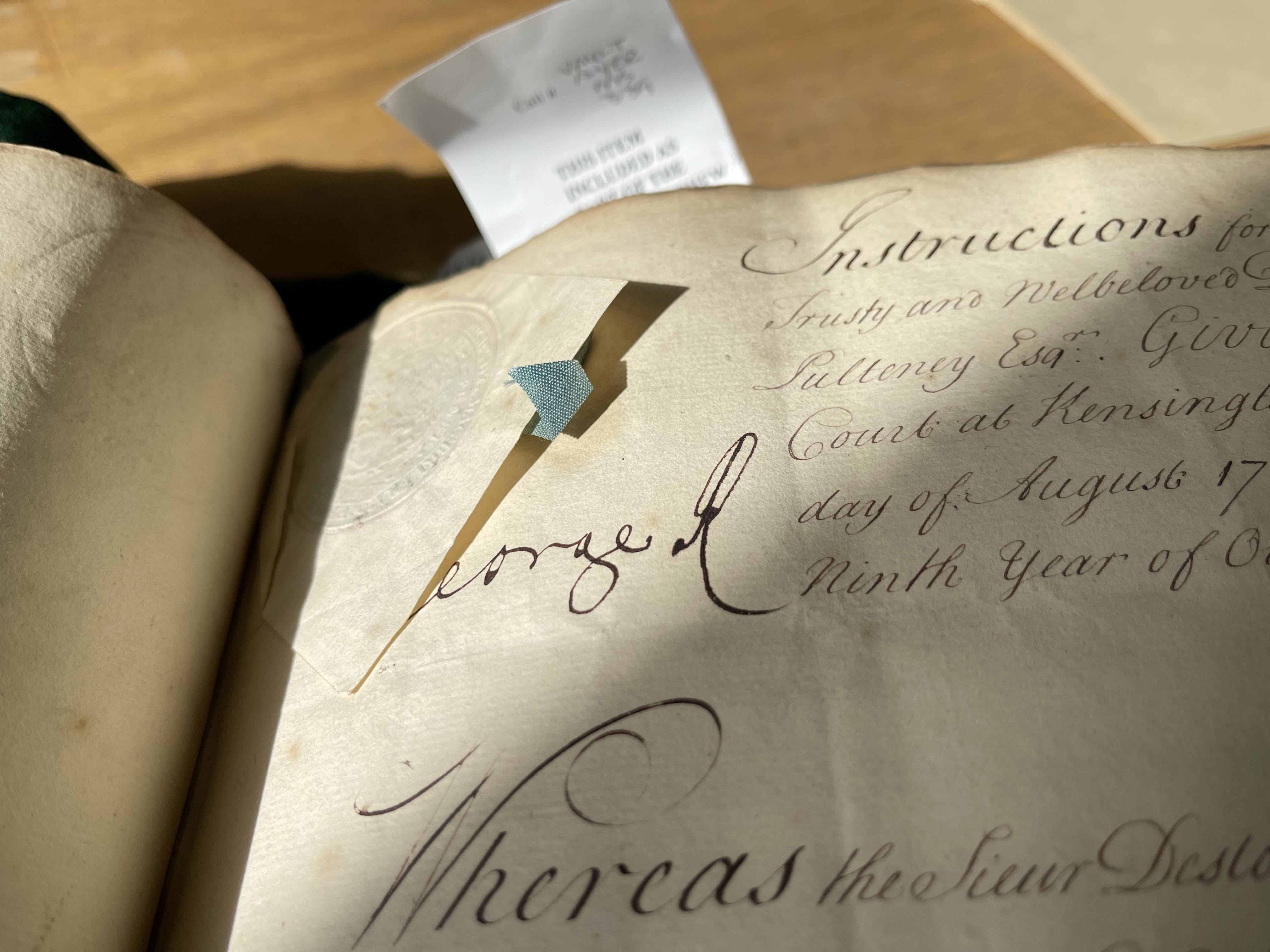

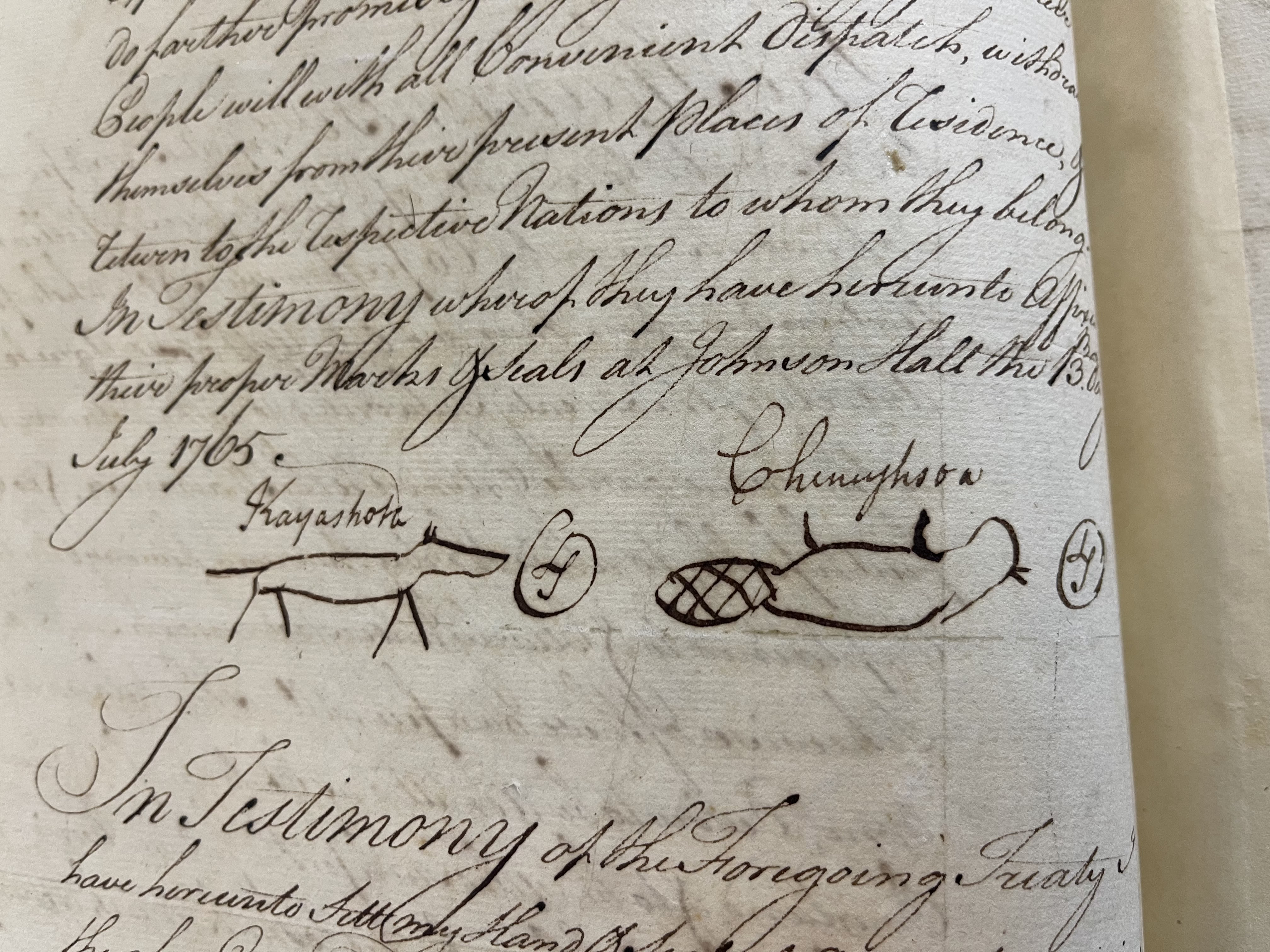

Other large projects by the Group have kept the focus on Indigenous oral traditions and their ongoing power articulated through treaties. Brightening the Covenant Chain (BTCC) revealed the diplomatic history of the British Crown and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the influential group of Indigenous nations who dominated northeastern North America up until the 18th century. Timed to correspond with the 260th anniversary of the first ‘special relationship’ between American and Britain embodied in the ratification of the Treaty of Niagara in 1764, the project worked to ‘brighten’ or rekindle one of the world’s oldest diplomatic relationships. It did so via museum exhibitions and creative residencies, new research publications, a commissioned film and a ceremonial Gasweh:da, or wampum friendship belt made by Haohyoh (Ken Maracle, Cayuga Nation, Deer Clan) as a living symbol and reminder of treaty. The project placed a spotlight on the Indigenous diplomatic methods and protocols that bind the British King in an abiding kinship relationship or metaphorical ‘Covenant Chain’ with the Haudenosaunee. These treaty relationships were eroded by ensuing Canadian governments, something many Haudenosaunee people view as a usurpation of their primary nation-to-nation agreements with the Crown.

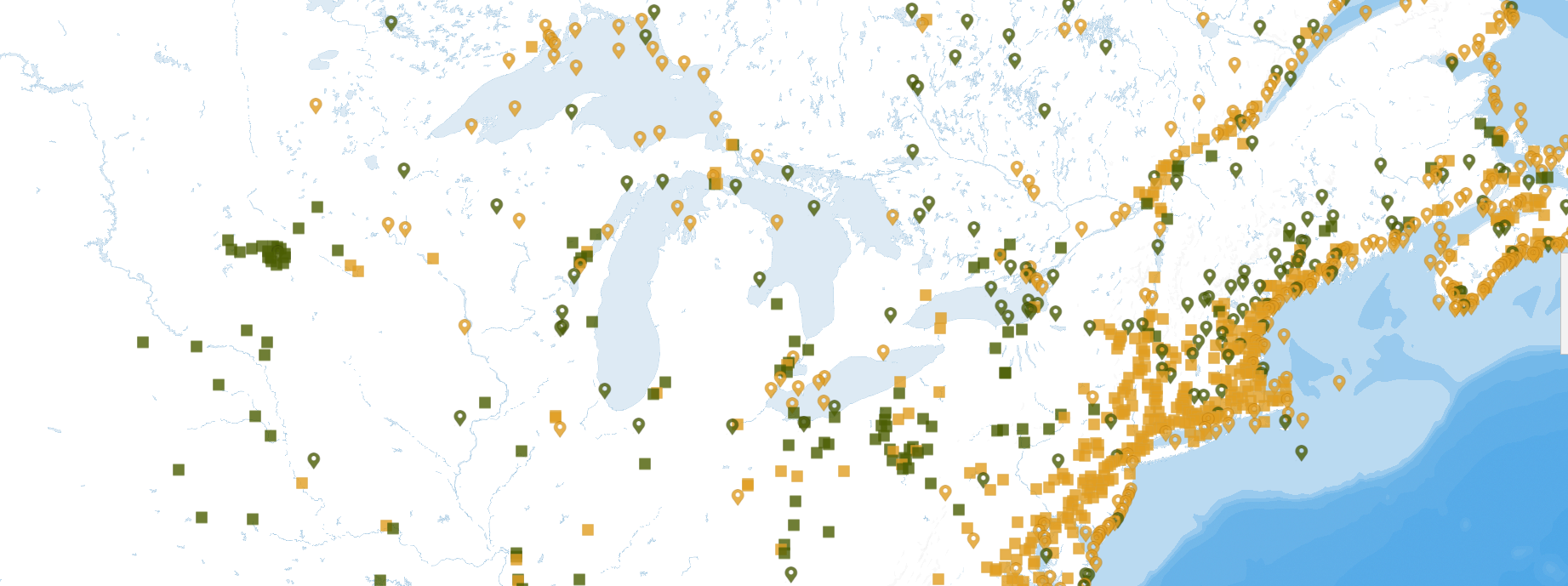

The researchers have visualized these relationships using a dynamic interactive map of Indigenous settlements and activities in the American northeast called Movement and Common Worlds. The resource—co-developed with Indigenous communities and King's College London’s Digital Lab—showcases the boundaries of Indigenous-colonial interaction, traditional routes of movement before and after colonial treaties, the gradual hardening of borders, and how the cultural landscape of the region changed over more than two centuries.

It was created by georeferencing historical maps from the British Library with archival data, explains Professor Porter. “After 1776, the Americans essentially erased Indigenous communities from their mapping, but the old British maps still contained valuable Indigenous place names and metadata that we have incorporated into this new map,” she says. “On our map, a person from New York, for example, can locate their home and see what major Indigenous settlements were nearby in the past, what the key place names were, what locations were and remain spiritually significant, where people moved goods and traded, and so on.” The resource, she argues, challenges the notion that American map-makers were so keen to present, that colonial settlement quickly erased the Indigenous presence from the continent. In fact, each British map-based depiction of the ‘colonial world’ was also a depiction of an Indigenous one. The project brings these worlds back together after two centuries of separation.

Treatied Spaces is further promoting Indigenous diplomatic history through a series of immersive soundscapes. Whereas Western cultures tend to rely on written histories, much Indigenous history and culture is transmitted orally, and has therefore often been omitted or corrupted within the historical records of colonizing powers. The Voices at the Edge of the Woods soundscapes document aspects of that oral history, recreating diplomatic transactions between the British Crown and representatives of the Haudenosaunee Council. They include examples of ceremonially significant diplomatic speech and song delivered by Indigenous leaders during treaty negotiations. They are brought to life in both English and the Kanyen’kéha (Mohawk) language, to detail the treaty process between British diplomats and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in what is now New York/Canada.

“Since many Indigenous cultures have foundational oral traditions, bringing oral traditions into historical and political diplomatic consciousness is a key objective,” says Professor Porter. “This is especially important when it comes to treaties, as the words used in treaties often hold both spiritual and diplomatic significance.”

Joy filming at Mount Stewart

Joy filming at Mount Stewart

Global Spotlights

Professor Porter also works to globalize Indigenous voices as one of the Lead Editors of the Cambridge University Press book series Elements in Indigenous Environmental Research, alongside Professor Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes, California State University) and Dr Clint Carroll (Cherokee, University of Colorado). The series covers every continent and investigates the relationships between environmental issues and Indigenous socioeconomic, cultural, and political dynamics. Other Group projects include Professor Gregory Smithers' project Native Ecologies: A Deep History of Climate Change, which emphasizes the long history of Indigenous responses to climate fluctuations, identifying how we can draw on these historical responses for climate action today. Professor Charles Prior’s Treatied States of America: Interior Diplomacy and the Contest for (Native) American Resources, illustrates the role of Indigenous treaties in the geopolitics of U.S. energy and resources, revealing how they both limit and enable the governmental strategies that will shape the future.

Reframing Historic Houses

Library at Cladeboye Estate

Library at Cladeboye Estate

The latest large internationally collaborative project underway from Professor Porter and the Treatied Spaces Group is Historic Houses, Global Crossroads. It sheds light on the role of historical properties in intercultural exchange. Many European historic properties and their extensive grounds, house materials, artifacts and plants were either taken from Indigenous peoples, or gifted by them as symbols of sovereign nation-to-nation diplomatic exchange. The project is revealing the textured flows of interconnection and important links between global communities they embody.

The project focuses on two of Northern Ireland’s most globally-significant yet under-researched heritage sites in the contested political context of Northern Ireland. One is Clandeboye Estate, which is privately-owned, and the other is Mount Stewart, looked after by the National Trust. The challenge of globalizing these spaces has vital significance in a part of the U.K. where historic houses are embedded in a long history of empire, internal colonialism and sectarian division. The aim is to make these heritage sites unfamiliar again as global crossroads, repositioning them as part of international society. “The goal is to ensure that when people from diverse backgrounds, whether Indigenous, Chinese, South or SE Asian, visit these properties, they will find meaningful connections and representations of their culture,” says Professor Porter.

The project is carrying out a field-leading econometric Visitor Choice Modelling Cultural Value Analysis to help the sites decide on how they might develop along these lines in the future. The intention is to co-produce models with the heritage sector that allow these sites and their ecologically significant grounds to transform into entangled locales of diplomacy, international ecological exchange, interconnection, identity reflection and formation.

Future Treatied Spaces

The group continues to deepen understanding of both historic and contemporary treaties as living and contested instruments of inter-cultural diplomacy. Professor Porter is working with colleagues at Harvard Law School exploring how treaties might figure within a developing new paradigm based upon recognition of the legal incommensurability between a significant proportion of Indigenous legal systems and Western-centric international law. She is also exploring with Indigenous colleagues at the University of Ottawa, how Indigenous, treaty and ‘rights of nature’ approaches could help solve the world’s freshwater access crisis and its associated threats to well-being. The aim is to co-produce the first ‘canon’ of Indigenous relational water governance advanced in ecologically important regions transformed by colonialism.

“Treaties”, she concludes, “are central to the quest for social and environmental justice and are a foundation for renewed, more balanced relationships between Indigenous and settler communities. They shape our understanding of sovereignty over land, resources, peoples and environments on earth, in the seas, and in space. It is intellectually transformative to approach our globe and beyond as what they are - treatied spaces”.

Ohsweken Powwow

Ohsweken Powwow

This content was paid for and created by University of Birmingham. The editorial staff at The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.