Forging Partnerships: Pitt's Collaborative Efforts Shape the Future of Innovation

Exploring Pitt's Impactful Collaborations in Research, Biomanufacturing, and Life Sciences

Universities are not only in the regions they operate, but of them. We are our communities.

At the University of Pittsburgh, this is apparent in the partnerships we forge. Joining forces with private industry to ramp up biomanufacturing can be done in concert with offering education to the neighborhood about living therapies. Commercializing the game-changing discoveries from the lab can bring jobs and vitality to the region.

In some instances, our partnerships can literally help to build neighborhoods, creating new materials for structures and bridges, strengthening the very cores of our communities.

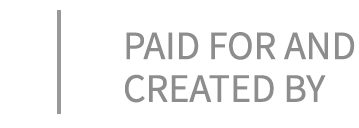

Amir Alavi, assistant professor in the Swanson School of Engineering, set artificial intelligence (AI) to the task of rethinking large-scale civil engineering projects. It led to the development of never-before-seen structures with properties no one could have guessed. It also led to partnerships with the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission and Department of Transportation (DOT).

Amir Alavi, assistant professor in the University of Pittsburgh’s Swanson School of Engineering, is partnering with the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission and Department of Transportation

Amir Alavi, assistant professor in the University of Pittsburgh’s Swanson School of Engineering, is partnering with the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission and Department of Transportation

In a paper published in Advanced Intelligent Systems, Alavi outlined a platform to use AI to mimic the most natural of all processes, evolution by natural selection.

The platform used generative AI, similar to the technology underpinning ChatGPT, to create these new materials called metamaterials. They ranged from basic structures like those commonly found in materials science labs to intricate shapes reminiscent of ancient scripts found etched on a clay tablet.

“Some of these structures are just so complex and inconceivable by the human mind,” Alavi said. “Yet they provide excellent mechanical performance, better than all the other solutions we’ve come up with before.”

Alavi’s long-term vision is to harness the power of generative AI tools to reshape America's civil infrastructure. He says metamaterials are a perfect fit for large-scale infrastructure projects because small improvements in weight or strength add up quickly over industrial-sized structures.

In two first-of-their-kind projects, his team is building megastructures from metamaterials. He partnered with the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission to design noise-dampening walls that will also capture some vehicle emissions. And he has contracted with the DOT to design bridge decks.

One of the ways in which Alavi’s platform differs from ChatGPT is that it does not need to be trained on vast amounts of data. In fact, it does not need to be trained on any data at all. Like natural selection, it began with just two parents — two shapes. They came together, a bit of randomness was thrown in and, if the resulting shape had the property Alavi was looking for — strength or flexibility, for example — it moved on to the next round.

"The platform isn’t limited to creating stronger concrete or better building materials. It could model a molecule or a neuron or, who knows, maybe the evolution of an entire living organism. That’s part of its beauty,"

“We can fit anything into this system and see how it morphologically evolves. We may find solutions never seen before. All we need is a single piece of a system to launch the evolutionary process.”

While evolution is a great model for discovery, when it comes to production, timeliness and precision are often key. But they don’t come cheap.

For precision biological medicines such as CAR-T therapies — which use a patient’s own re-engineered immune cells to fight cancer— it can cost nearly half a million dollars to manufacture a single therapeutic dose. Pitt’s new biomanufacturing innovation facility, BioForge, will work on ways to reduce the cost of these and other existing and emerging precision biological medicine by as much as 10 times, making them accessible to more patients, more quickly.

BioForge will work on innovations to reduce by ten-fold the cost of these and other existing and emerging precision biological medicines, making them available faster and to more patients.

The facility, underway at Hazelwood Green, the site of Pittsburgh’s last operating steel mill, will accelerate breakthroughs in the manufacturing of new biologic precision medicines more efficiently and affordably, said its chief executive officer, Kaigham J. (Ken) Gabriel, an engineering and life sciences entrepreneur who brings a wealth of experience in government, academia, and the commercial sector.

“Ken’s depth of experience as an innovator across government, academic and commercial sectors makes him a perfect fit for leveraging Pitt’s world-class research in medicine and the health sciences at BioForge,” Anantha Shekhar, senior vice chancellor for the health sciences and John and Gertrude Petersen Dean of the School of Medicine, said in announcing Gabriel’s appointment.

The founding anchor tenant at the facility, ElevateBio, a Massachusetts-based biotech company, will lease about 70% of the site’s 175,000 square feet of space for a commercial gene and cell therapy bio-manufacturing hub to be called Basecamp Pittsburgh.

“As a society, we often celebrate new inventions while overlooking the ingenuity and passion required to deliver them. Manufacturing precision medicines will require innovations just as potent as those that led to their invention,” Gabriel said. To create those innovations, he said, “You’re going to need life scientists, biologists, you're going to need engineers, you're going to need physical scientists, you're going to need people with AI machine learning— all working together to focus on specific quantitative objectives associated with manufacturing at scale.”

BioForge is expected to lead the way in life sciences manufacturing innovation, bringing together the diverse disciplines of the university with the broader capabilities of the region and private sector as an example of what’s possible at Pitt.

To reinforce this synergy, Pitt created LifeX, an LLC focused on supporting and de-risking burgeoning businesses in the life sciences, while giving them a reason to stay here in Western Pennsylvania.

LifeX partners with early-stage life sciences companies from anywhere —not just Pitt — by providing a basic level of support, mentorship, and early-stage risk capital to keep companies local. For example, a 13-week program helps teams working on commercializing technology in digital health, medical devices or therapeutics.

“This kind of support is particularly important in the life sciences, which often require extensive interaction with regulatory agencies like the FDA”, said Evan Facher, vice chancellor for innovation and entrepreneurship. It’s a very different beast than starting a travel company or a robotics factory.

Evan Facher, vice chancellor for innovation and entrepreneurship at The University of Pittsburgh.

Evan Facher, vice chancellor for innovation and entrepreneurship at The University of Pittsburgh.

In 2023, LifeX received a $2 million grant through the Build to Scale program that administers funds through the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration (EDA). The program is intended to accelerate technology entrepreneurship, and it will allow LifeX to make a larger impact in the life science startup ecosystem locally, nationally and globally.

Also last year, via the Office of Industry and Economic Partnerships, the university formed a partnership with bioMérieux, a worldwide leader in in-vitro diagnostics and testing solutions for infectious diseases. The relationship will engage the French company’s analytical and sequencing team with Pitt’s Division of Clinical Microbiology and Division of Infectious Diseases to improve diagnostics and, patient health.

Through these channels, ultimately, Pitt and LifeX are partnering with the community. Helping researchers solve the biggest challenges in health and medicine while keeping their businesses in Pittsburgh is a win for everyone.

“Almost every newly ceated-job in the commonwealth is from a new company,” said Facher, who is also associate dean for commercial translation in Pitt's School of Medicine. Keeping spinoff companies in Pennsylvania means adding jobs, too.

“We want these two, three, or five-people companies to become 20, 30, or even 500-people companies.”

Learn more about the partnerships forged at Pitt

This content was paid for and created by The University of Pittsburgh. The editorial staff of The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.