Beyond the Lab:

How Florida Atlantic Turns Research into Real-World Change

As Florida Atlantic University, in Boca Raton, Fla., celebrates its new Carnegie classification as an R1 research institution, scientists at the university are demonstrating a systematic approach to turning academic discoveries into public policy that improves lives. While many colleges contribute to scientific knowledge, Florida Atlantic has developed strategies to ensure that the research it produces leads to real-world change.

Build Research Around Public Good

"Science is only as good as the way it can be utilized by the public," says Gregg Fields, Ph.D., Florida Atlantic's vice president for research and executive director of the university's Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention (I-Health). "You need to think about making it useful: what expertise you need and what the end users, like policymakers or clinicians, expect to see."

Gregg Fields, Ph.D.

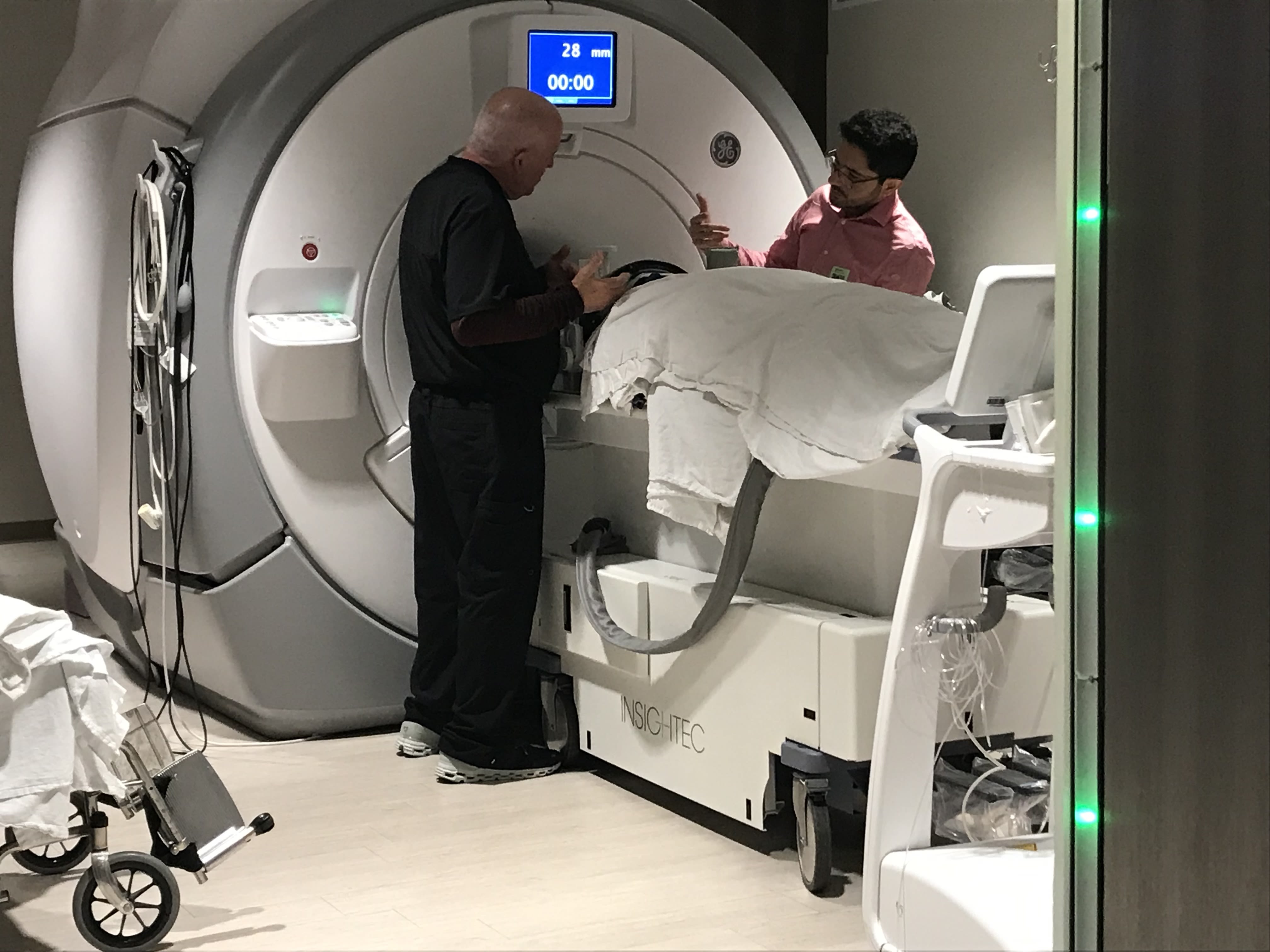

This philosophy drives how the university approaches research from the earliest stages, focusing on projects with clear pathways to public benefit. Consider its pioneering Alzheimer's treatment trial — a collaborative initiative between I-Health and Delray Medical Center. The research began with a fundamental challenge: According to Fields, less than one percent of currently available drugs for Alzheimer's treatment typically cross the blood-brain barrier, forcing doctors to prescribe high doses that often cause serious side effects.

By using focused ultrasound technology to help medications cross this barrier more effectively, the trial aims to reduce both dosages and side effects. In one early result using the drug Aducanumab, areas of the brain treated with focused ultrasound showed 80-percent removal of harmful beta amyloid proteins, compared to just 10 percent in untreated areas. By improving medication delivery to the brain, this technique could allow for lower drug doses while achieving better results, potentially revolutionizing Alzheimer's treatment for millions of patients.

This emphasis on practical impact extends across the university's interdisciplinary research portfolio. At Florida Atlantic's Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, scientists study how water quality and marine life affect public health and Florida's economy. Through Canines Providing Assistance to Wounded Warriors (C-P.A.W.W.®), an I-Health initiative, researchers examine how service dogs could provide veterans a more effective alternative to traditional treatments for PTSD and traumatic brain injuries.

Understand Community Needs

Successful policy-focused research requires deep understanding of the communities it aims to serve. At Florida Atlantic, this means engaging with constituents before research begins and maintaining dialogue throughout the process to ensure findings address real needs.

Fields has seen how different research resonates with different communities: "When meeting state policymakers, you have to understand not just their priorities, but also their constituents' concerns. Our Alzheimer's research resonates deeply with policymakers representing elderly populations, while water-quality issues like harmful algal blooms are critical among populations in coastal areas."

For the Alzheimer's treatment trial, this meant examining how current treatment limitations affect both patients and caregivers. High medication doses don't just cause side effects — they increase treatment costs and often lead to reduced compliance, creating cascading impacts on families and healthcare systems. By understanding these challenges early, researchers could design studies specifically addressing these community concerns.

James Sullivan, Ph.D., executive director of Harbor Branch and a member of Florida's Blue-Green Algae Task Force, studies one of the state's most pressing environmental challenges: harmful algal blooms that choke waterways, kill marine life, and threaten both human health and tourism. This research also began with community impact.

"We had many state agencies and different people come and essentially testify to us in open meetings," Sullivan explains.

This input revealed how blooms affect various stakeholders — from tourism workers facing lost income to waterfront homeowners dealing with property damage to public health officials managing community health risks.

"After we heard everything we could from state agencies and scientists, we then got together and said, 'Okay, if we had unlimited money and wanted to concentrate on various ways of cleaning up this problem, this is what we'd concentrate on first.'"

The C-P.A.W.W. program also demonstrates the impact of direct engagement with constituents.

"Our projects start with the veteran community's needs," explains Cheryl Krause-Parello, Ph.D., professor in Florida Atlantic's Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, and founder and director of C-P.A.W.W. "I continually seek input from veterans to ensure our studies address their real concerns."

Cheryl Krause-Parello, Ph.D.

By working directly with the veteran community, C-P.A.W.W. helped identify key issues — like the high costs of obtaining and maintaining service dogs — while also revealing unexpected insights about how these animals help veterans integrate back into civilian life.

"These dogs save their lives," Krause-Parello emphasizes. "And they save their lives every day just by having that presence of a non-judgmental being with them."

By putting affected communities at the center of research decisions, Florida Atlantic ensures its work addresses real needs rather than assumed ones. This approach strengthens the research itself and makes findings more compelling to policymakers seeking to understand how legislation will impact their constituents.

Assemble Interdisciplinary Expert Teams

Addressing the complex needs of communities requires bringing together diverse expertise, including laboratory scientists, clinicians and policy experts. Florida Atlantic structures these collaborations through its four research institutes — I-Health, Harbor Branch, the Stiles-Nicholson Brain Institute, and the Institute for Sensing and Embedded Network Systems Engineering — each combining different perspectives while maintaining clear pathways to policy impact.

As an example of what interdisciplinary research looks like on campus, Fields points to I-Health's approach to developing cancer treatments.

"When developing our cancer program, we had to bring together components ranging from basic research to translational research to clinical research," explains Fields. "You need basic scientists working alongside clinicians who can say whether something is practical. For example, you may discover a compound that works well against cancer. But if it requires 60 steps to synthesize, it will never be practical as a drug; it would be too expensive to make. You need that clinical perspective early in the process."

This same principle guides the Alzheimer's treatment trial, in which I-Health researchers collaborate with Delray Medical Center clinicians to ensure laboratory findings translate into practical treatment protocols. The trial's early success in improving medication delivery to the brain stems directly from this combination of research expertise and clinical experience.

Addressing the impact of blue-green algae blooms also requires an interdisciplinary approach, with oceanographers studying bloom formation, ecologists examining environmental impacts, and experts in hydrologic modeling predicting bloom patterns.

Similarly, C-P.A.W.W. brings together interdisciplinary researchers and clinical practitioners, with a team including military veteran consultants, community liaison coordinators, and research staff with expertise in both biological and psychosocial assessment.

"You need multiple perspectives to understand how service dogs impact veterans' lives," Krause-Parello notes. "It's not just about measuring stress markers: You need to understand the practical challenges veterans face and how policy changes could help."

When research teams include voices from across disciplines — and particularly those with practical implementation experience — they're better positioned to develop solutions that work in the real world.

Translate Research Into Actionable Recommendations

Understanding public impact and assembling expert teams creates strong research foundations. But influencing policy requires translating complex scientific findings into recommendations that resonate with policymakers' priorities and their constituents' needs.

"You have to be able to translate scientific research into everyday terms," Krause-Parello emphasizes.

Krause-Parello has refined this approach over a decade of advocacy, beginning with C-P.A.W.W.'s founding at the University of Colorado's College of Nursing in 2013 before bringing the program to Florida Atlantic in 2018. She combines hard data, like biological stress markers and quantitative surveys, with powerful personal testimonies from veterans about how service dogs have transformed their lives. When presenting to Colorado legislators, she brought veterans and their service animals to the statehouse, allowing policymakers to hear firsthand the impact of the research. This helped to secure passage of legislation funding service dogs for a group of veterans with PTSD. Her success in Colorado now serves as a model for her continued advocacy in Florida and at the federal level.

Sullivan's work on harmful algal blooms shows how similar principles can shape environmental policy. The Blue-Green Algae Task Force combined scientific evidence with community input to create clear, actionable recommendations. By translating complex scientific findings into specific policy proposals, the task force helped legislators understand both the scope of the problem and potential solutions. Shortly after, the government created the Florida Clean Waterways Act, which established new regulations for wastewater treatment, stormwater management, and agricultural runoff to reduce the nutrients feeding algal blooms.

These successes demonstrate how universities can create sustained partnerships between researchers and policymakers. Florida Atlantic's recent R1 designation strengthens these relationships.

"When I go to Tallahassee, it helps to say 'We've achieved this level of research excellence,'" Sullivan notes. "It gets policymakers to take us more seriously."

This recognition matters because government funding — both state and federal — drives much of the university's research agenda.

"In the past 20 years, there's been a shift in sponsored research," Sullivan notes. "It's no longer just basic research where someone works in their lab and makes a discovery. Now, it's very societally relevant — research has to have some application in making the world a better place."

This targeted engagement is part of a larger cyclical relationship between research and policy that Sullivan describes: "Scientists recommend policies, governments fund research aligned with policy goals, and that research then informs the next policy decisions."

Rather than moving in one direction — from lab to law — the process is reciprocal. Government priorities help shape research directions, while research findings guide policy recommendations and future funding priorities.

Create Lasting Impact

The elevation to R1 status marks an important milestone for Florida Atlantic. As higher education institutions nationwide seek to demonstrate their research relevance, the university's systematic approach offers a roadmap for others to follow. Through intentional focus on public impact, strategic community engagement, interdisciplinary collaboration, and effective policy translation, universities can ensure their research doesn't just advance knowledge — it creates meaningful change in the communities they serve.

The model also demonstrates how campuses can maintain academic rigor while informing policy intended to benefit the public good.

James Sullivan, Ph.D.

"Scientists truly do care about making the world a better place," Sullivan reflects. "We live in this environment too, and we want it to be good for our families. If we can help, we will."

This content was paid for and created by Florida Atlantic University. The editorial staff of The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.