Answering the Call

How one trailblazing professor is bringing new life to neuroscience at UVA

When the University of Virginia began offering neuroscience as an undergraduate major in 2003, it was among the first schools in the country to do so. The cutting-edge program, started by a handful of faculty in the psychology and biology departments, was minimally funded at the outset and, by any standards, small in size, accepting only 20-25 students a year. Nonetheless, it helped distinguish UVA in the early 2000’s as a place where at least some undergraduates could collaborate with senior faculty and engage in meaningful research.

With the program’s initial success, came increasing popularity, particularly among pre-med students, followed by an inevitable call for university resources. To compete with the emergence of top neuroscience programs across the country, UVA would need to invest significant capital in the renovation of Gilmer Hall, home to its psychology and biology departments. The need for experiential and team-based learning spaces and open lab environments for interdisciplinary collaboration was pressing. And perhaps most importantly, the program called for several key faculty hires.

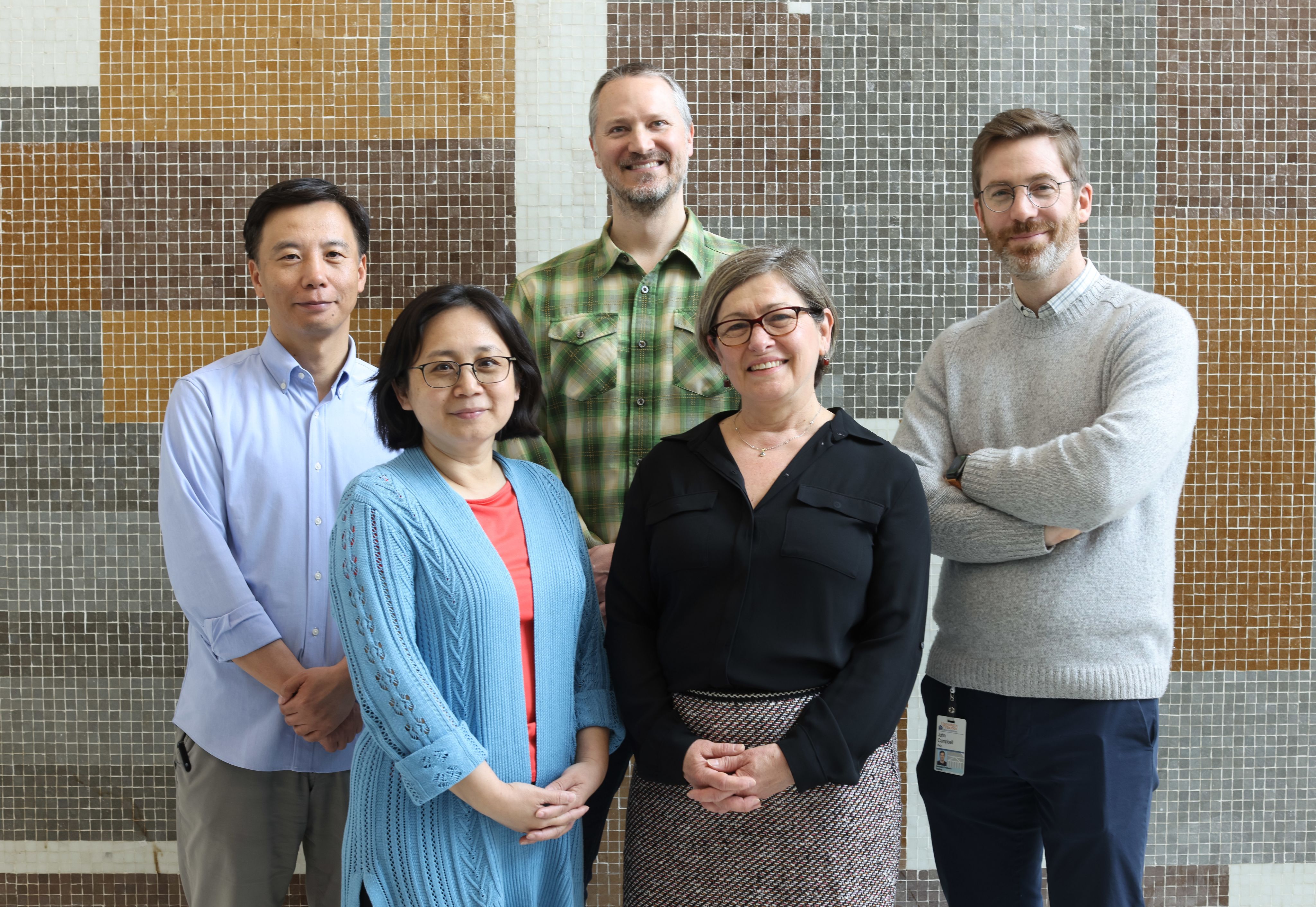

JC Cang partners with a team of talented psychologists and biologists at UVA, pictured here (from left to right: JC Cang, Xiaorong Liu, Per Sederberg, Alev Erisir, and John Campbell).

JC Cang partners with a team of talented psychologists and biologists at UVA, pictured here (from left to right: JC Cang, Xiaorong Liu, Per Sederberg, Alev Erisir, and John Campbell).

Among the first to answer the call for support was the Jefferson Scholars Foundation.

Widely known for attracting exceptionally talented students to UVA through its longstanding merit scholarship competition, the Foundation began setting its sights on a new effort to support the University in 2011. Through a series of $5 million endowed professorships, the Foundation aimed to help recruit to UVA a talented cadre of faculty across multiple fields of study. By 2015, its first endowed professorship was fully funded just as the neuroscience program was reaching an inflection point. The University was eager to put the money to use and began searching for a rising star in the field.

For both the University, which sought to bring long overdue distinction to the neuroscience program, and the Foundation, which was eager to set the bar high for its newest effort, getting the hire right was essential. After an extensive national search, both parties, it seems, came out on the winning side.

In 2017, Jianhua "JC" Cang, a neurobiologist at Northwestern University, joined UVA as the inaugural holder of the Paul T. Jones II Jefferson Scholars Foundation Distinguished Professorship.

At Northwestern, Cang’s lab had been making waves in the field of neuroscience for the better part of a decade. His research, which examines the organization, function, and development of two brain structures in the visual system—the cortex and the superior colliculus—takes an integrative approach that combines physiology, functional imaging, mouse genetics, molecular, behavioral, and computational methods to identify treatments for visual impairments.

Cang and his Northwestern colleagues recently had made two breakthrough discoveries that were introduced into textbooks—effectively putting Cang on the shortlist of top neuroscience programs across the country. Their work demonstrated that a period of plasticity in early development is central to how neurons interact and function in the visual system later in life. They discovered neurons that are selective to specific features of stimuli and match their binocular selectivity during early development in an experience-dependent manner. The National Institutes of Health also took note, awarding him more than $1 million in research funding from its Eye Institute.

When Cang got the call from UVA, he was not necessarily looking to uproot his family or change schools, he says, but he was compelled by the invitation for several reasons.

“For starters, I knew that being supported by the Jefferson Scholars Foundation would mean I would have a pretty decent size of start-up funding, which would allow me to build a team of post-docs and a lab of cutting-edge instruments. I knew we would be backed to try something risky or something that isn’t yet supported by federal grants,” he said.

“But I also was excited to learn that there was an opportunity to create a number of potential new collaborations.”

Cang’s offer included joint appointments in psychology and biology, a fairly uncommon arrangement at UVA, which put him in a unique position to collaborate with colleagues across multiple specialties. As such, he was charged with doing exactly that. The idea was that his position would help bridge the two departments and, in turn, shore up the curriculum for the neuroscience program.

Today, Cang is accomplishing all that the position calls for, and more. Not only has he designed several new courses, including the student-favorite “Neuroscience Through the Nobels,” an overview of the Nobel-winning discoveries that have profoundly shaped the field, but he also runs a state-of-the-art lab and dedicates much of his time to advising students as the director of the neuroscience undergraduate major. Under his leadership, the program has more than doubled in size, increasing from 20-25 students to 51 students in 2022 and 83 students in 2023.

Cang attributes his success at UVA, in part, to three key collaborations.

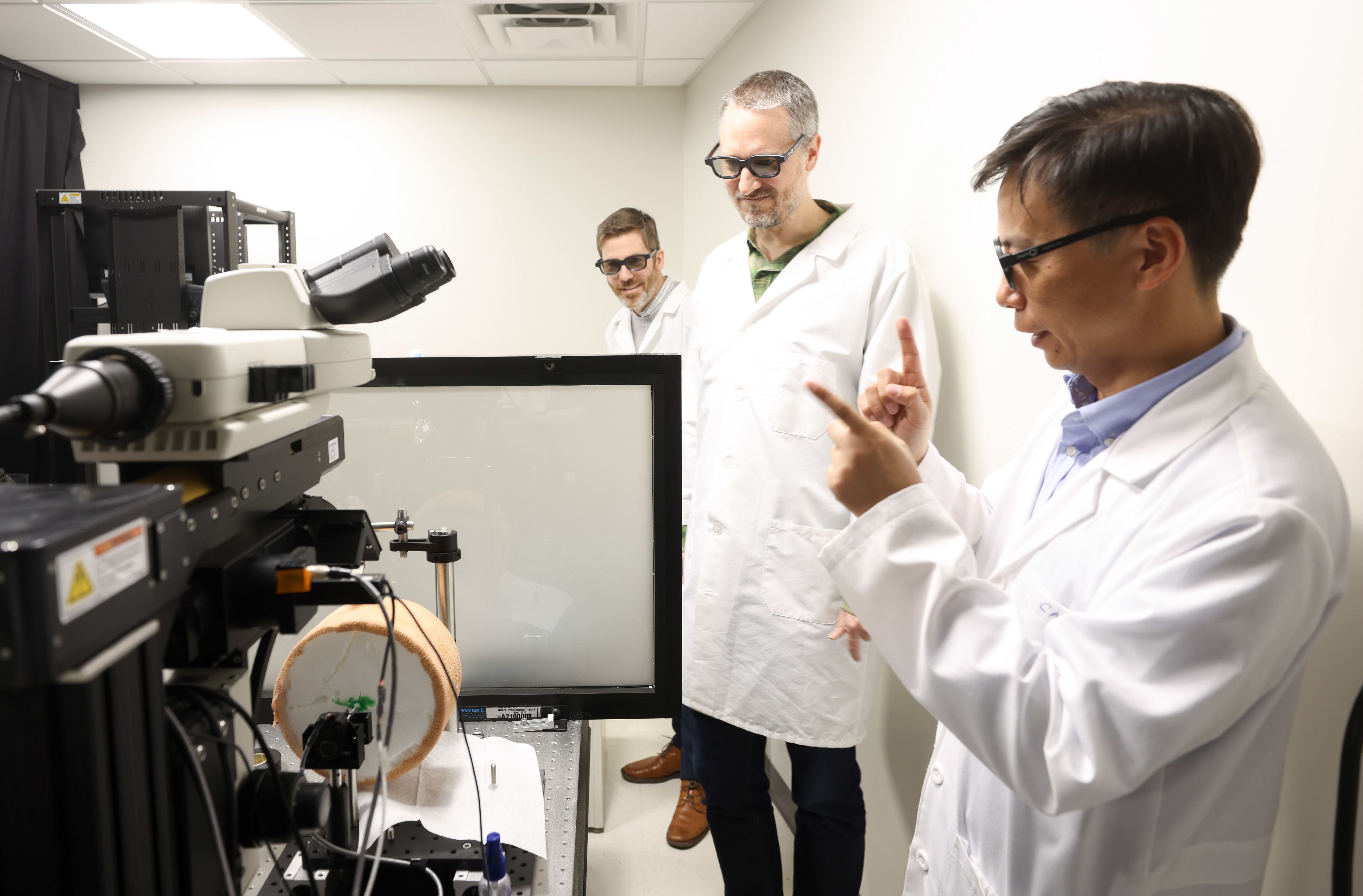

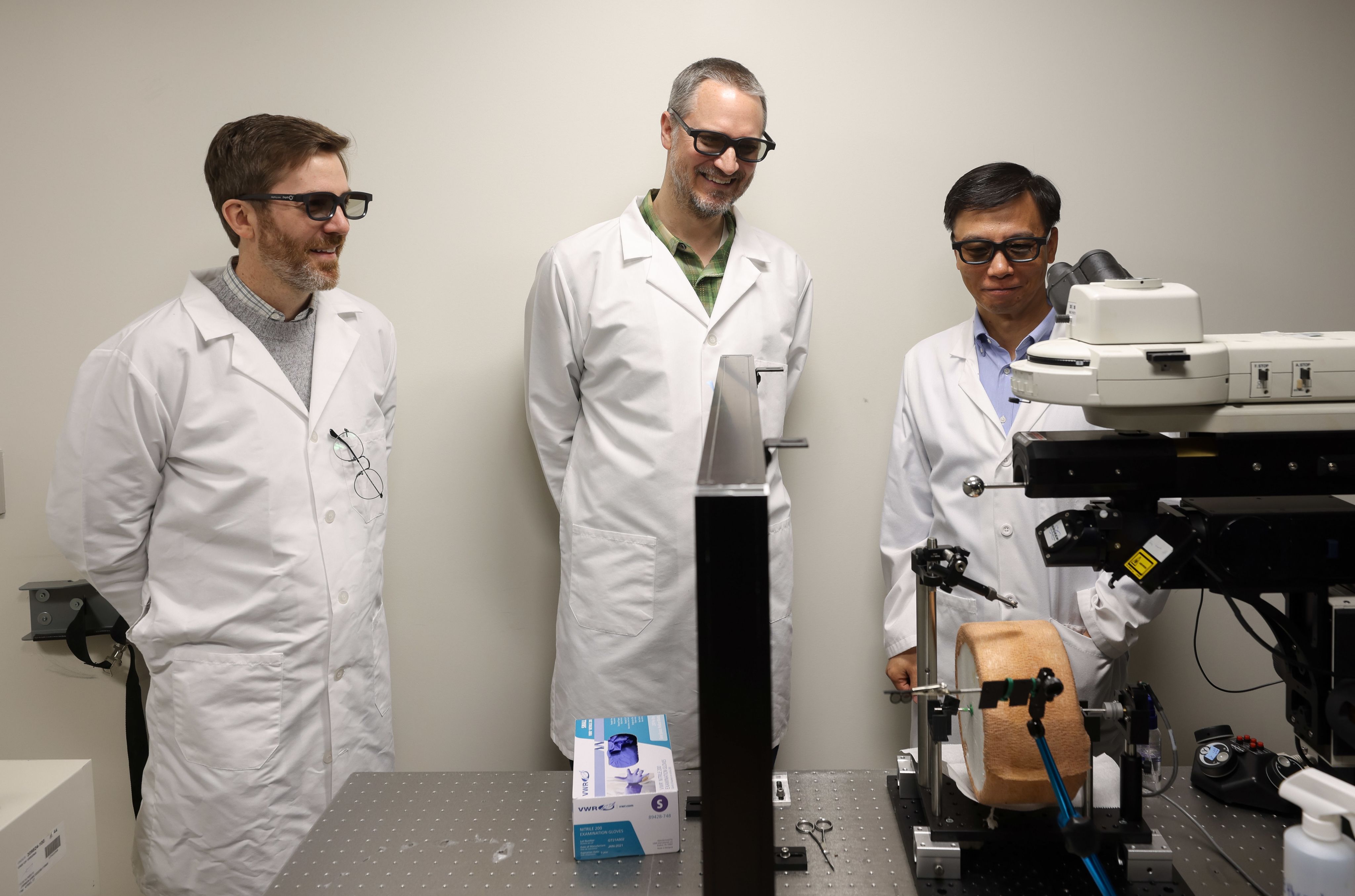

Campbell, Sederberg, and Cang operate the 3D visual projection system in Cang’s lab.

Campbell, Sederberg, and Cang operate the 3D visual projection system in Cang’s lab.

As chance would have it, Cang’s arrival to UVA coincided with the quiet phase of the school’s current $5 billion capital campaign. So, in addition to the funds from the Foundation, Cang would benefit from an influx of support for the sciences. In 2017, the same year as Cang’s arrival, the University launched a much-needed renovation of Gilmer Hall to the tune of approximately $200 million.

In its new, open-design space, Cang’s lab seems to stay abuzz with an almost constant flow of scientists, researchers, and students working simultaneously on one project or another. The area of the lab that most visitors want to see, Cang explains, is the small room that houses the 3D visual projection system. There, researchers place mice on a large dome and expose them to projections of three-dimensional moving images. The animal’s responses are in direct correlation with the visual stimuli, which helps Cang and his team understand how neurons in the brain respond to visual stimuli.

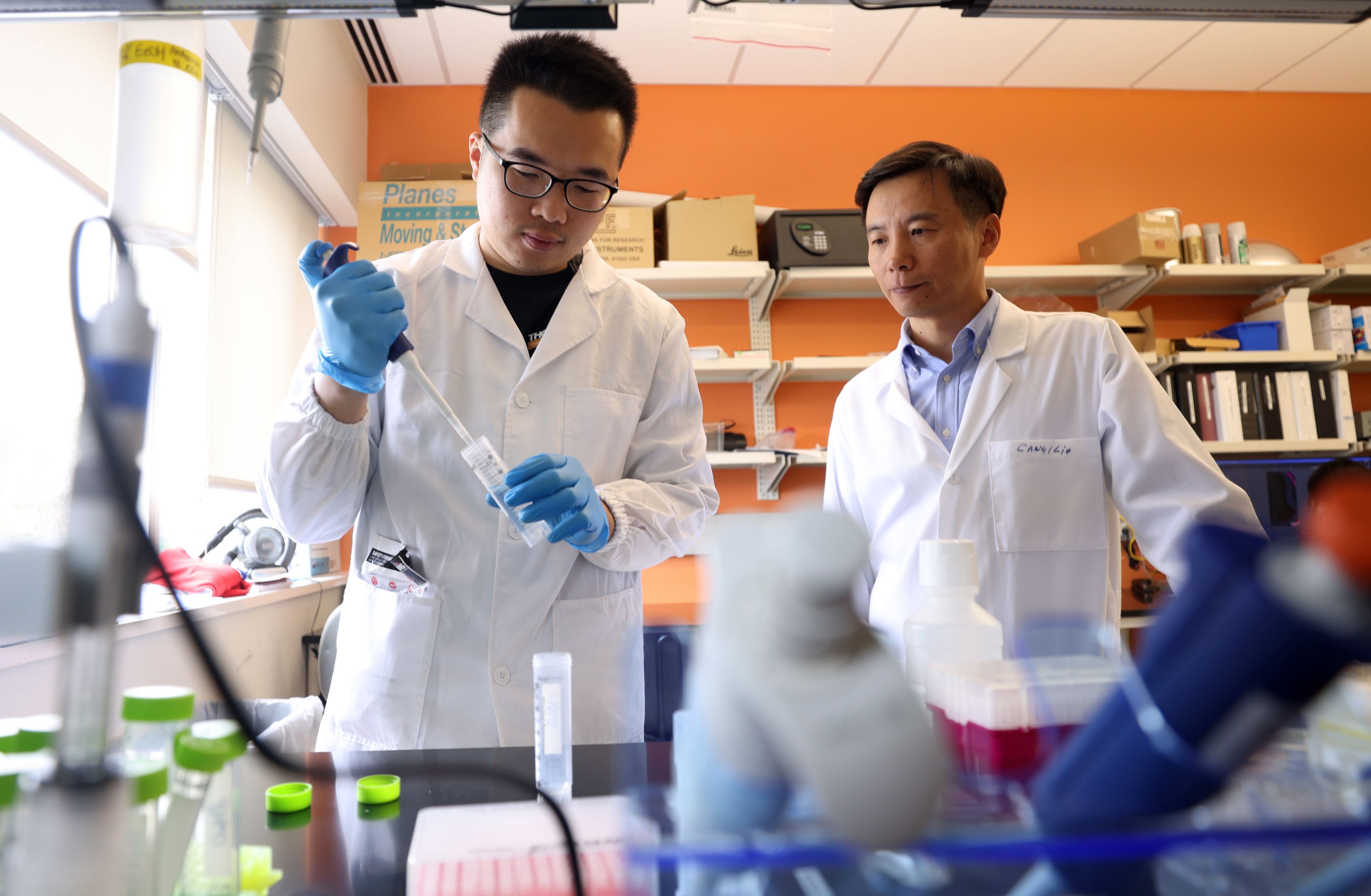

JC Cang advises graduate student Yuanming Liu in the lab.

JC Cang advises graduate student Yuanming Liu in the lab.

Cang’s new lab is adjacent to five others. One belongs to biology professor John Campbell, who is one of his three primary collaborators. Campbell’s research, which examines the neural circuits that control different functions of the digestive system, speaks to the work that Cang’s lab is doing on the visual system. Their proximity makes it especially easy to share both equipment and findings in real-time.

“I love the idea of putting us all in the same space because we all have complementary expertise and complementary technology,” said Campbell. “It’s an ideal partnership.”

Cang clearly agrees. One of his graduate students in biology, Yuanming Liu, also funded by the Jefferson Scholars Foundation, supports both him and Campbell. Liu helps identify cell types of the superior colliculus. Together, Cang and Campbell co-advise Liu on his work.

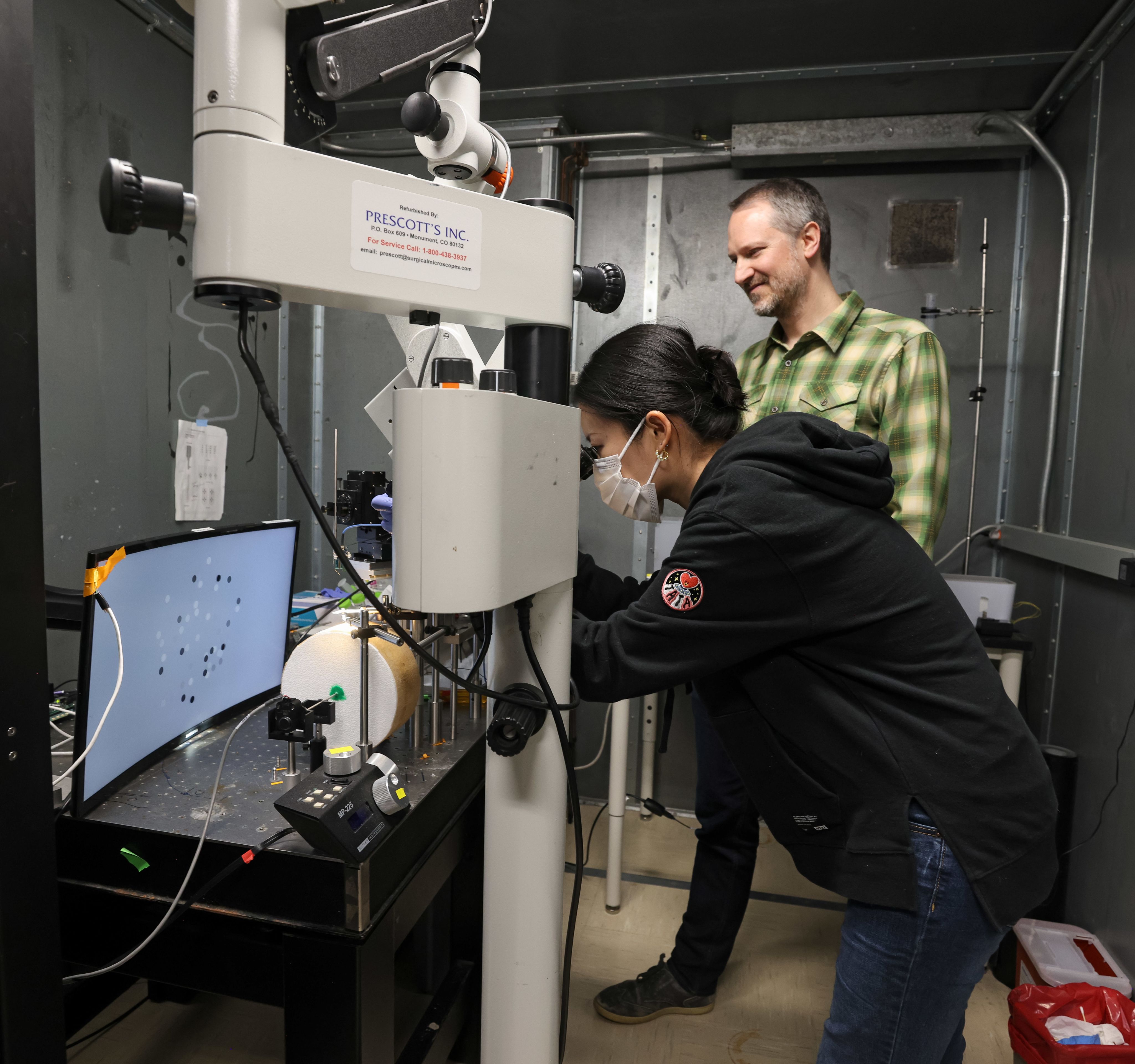

Cang formed a similar arrangement with Per Sederberg, a psychology professor who studies the computational mechanisms that underlie memory and cognition. A second graduate student funded by the Foundation, Chuiwen Li, works with and is advised by both Cang and Sederberg. Li is trained to integrate behavioral, physiological, and computational approaches in her studies.

“I think as much as any university I’ve ever known there’s opportunity at UVA to co-mentor students,” said Sederberg. “It benefits the professors certainly, but it also benefits the students. They can customize their own research and work in labs with combined expertise.”

One of the most impactful collaborations that Cang has forged is with psychology professor Alev Erisir, In fact, one of the reasons he was drawn to UVA initially, Cang explains, is the work that Erisir and her team are doing. During his interviews for the position, he learned that Erisir had established a new animal model using tree shrews. These small mammals bear a striking resemblance to squirrels and are native to the tropical forests of South and Southeast Asia. They also happen to be the closest species to humans beside monkeys.

For Cang, the opportunity to study the tree shrew could prove instrumental as he seeks to identify ways to reopen the window of brain plasticity in order to treat a range of visual disorders.

As Cang enters into his sixth year at UVA, the neuroscience program enters into its 20th. By all estimations, the program has come a long way, and Cang and his colleagues are pleased with the work that has been done to elevate the field. When pressed about the future of the program, he admits there is still a great deal of work to be done.

“I’d like to see the program continue to expand and become accessible to even more students,” he said.

Last Fall, when faculty hosted an information session for interested first-year students, they expected to welcome 50-60 students. Four hundred showed up.

“If we can accommodate the growing interest and expand to more than 100 students per class in the next few years, I would consider that a huge win,” Cang said.

He is also quick to add, however, that the biggest challenge will be to manage that growth carefully and to maintain the tightknit community that has defined the program since its inception. “We will do everything we can to protect that,” he said, “but it is equally important that we give as many students as possible access to neuroscience.”

For him, the study of neuroscience is about more than a professional pursuit or a personal passion; it is an exercise in self-discovery. The questions neuroscience seeks to answer are essential to human existence.

“How we see, how we move, how we feel, and even how and why we make decisions—all of that can be explained through neuroscience. I can think of few disciplines worthier of our students’ time or our University’s resources,” he said.

Unwavering in his optimism, Cang is certain that there is an exciting future for neuroscience at UVA. If he is right, it is safe to say there is also an exciting future for Cang.

Per Sederberg works with graduate student Chuiwen Li as she looks through an electroscope microscope.

Per Sederberg works with graduate student Chuiwen Li as she looks through an electroscope microscope.

“How we see, how we move, how we feel, and even how and why we make decisions—all of that can be explained through neuroscience. I can think of few disciplines worthier of our students’ time or our University’s resources.”

Learn more about the Jefferson Scholars Foundation’s Distinguished Professorship Program here. This content was paid for and created by Jefferson Scholars Foundation. The editorial staff of The Chronicle had no role in its preparation. Find out more about paid content.