How Stony Brook Is Reshaping Global Conservation and Sustainability

Stony Brook, one of the nation’s top public universities, continues to extend its impact far beyond New York, to the global stage. With the University continuing to attract prominent researchers, it is playing an increasingly important role in expanding efforts in conservation, biodiversity, and sustainability across continents and oceans — solidifying its standing as a worldwide leader in advancing efforts to better understand this planet’s past in order to protect its future.

This momentum is evident through the work of the Turkana Basin Institute (TBI). In 2005, Stony Brook University and world-renowned paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey established TBI in northern Kenya to support students and researchers on prehistoric digs in that region — one of the world’s best for uncovering early human fossils. Leakey, the son of acclaimed paleontologists and archaeologists Louis and Mary Leakey, had focused his own work in that area for nearly 40 years, and had discovered much of the evidence upon which we base our understanding of human evolution.

For Leakey, the institute assured that his lifelong work would continue. For Stony Brook, the institute cemented the University’s growing commitment to global conservation and preservation.

Discovering the Origins of Mankind

Beginning in 1968, expeditions led by Leakey uncovered one of the most complete Homo habilis skulls ever found and one of the best-preserved skulls of Homo erectus. Perhaps his most extraordinary discovery was the 1.6-million-year-old, nearly complete skeleton of “Turkana Boy,” a Homo erectus youth. For his groundbreaking anthropological finds, he won a Hubbard Medal, National Geographic’s highest honor, in 1994.

Leakey is an outspoken advocate with a long track record of government service, serving in various capacities in the Kenyan government. As the Director of the National Museum of Kenya for over 30 years, Leakey was chiefly responsible for preserving Kenya’s natural and cultural history. Under his tenure, more than 200 fossils were uncovered at Lake Turkana.

Stony Brook recruited Leakey as a visiting professor of anthropology in 2002 and began developing the idea of TBI, of which Leakey is now chair. The following year, the University recruited acclaimed paleoanthropologist Meave Leakey, who discovered a previously unknown genus and species of early humans. In 2016, she won a Hubbard Medal for her discoveries and dedication to the field.

TBI has become a springboard for students and scholars to augment Leakey’s earlier discoveries. While at TBI in 2011, Stony Brook faculty Sonia Harmand and Jason Lewis uncovered stone tools, dating back 3.3 million years — the oldest tools ever discovered. For students studying abroad, the Institute’s field school offers a unique hands-on learning experience, a rare chance to explore how humans fit into the natural world from the very birthplace of humans.

Students’ views and insights can be “totally changed by three months in Kenya,” Leakey has said. “There’s a very deep impact.”

Leakey’s discovery of the Turkana Boy in Kenya was a groundbreaking contribution to the field of evolutionary biology. Photo: Courtesy of Turkana Basin Institute

Leakey’s discovery of the Turkana Boy in Kenya was a groundbreaking contribution to the field of evolutionary biology. Photo: Courtesy of Turkana Basin Institute

Protecting Ocean Wildlife Globally

That sort of lasting impact is what Carl Safina, an international leader in ocean conservation, also strives to create. Safina, a marine ecologist, is the endowed professor for nature and humanity in the University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences.

Safina has traversed the world to advocate for ocean wildlife, from studying humpback and killer whales off the coasts of the U.S. to exploring the impact of climate change and the fishing industry in the Arctic.

His work has had far-reaching national and international impact. In the United States, Safina helped spearhead campaigns overhauling U.S. fisheries laws. Globally, he led efforts to improve international management of fisheries targeting tunas and sharks, protect elephant seals and penguins in the Falkland Islands, and reduce the drownings of sea turtles and albatross from commercial fishing lines. Safina’s efforts ultimately helped pass a United Nations global fisheries treaty.

Safina is the award-winning author of seven books examining the relationship between humanity and the living world. His TED talk on the topic has logged more than two million views. He won the MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 2000, for his creative use of scientific and communication skills.

At Stony Brook, he established the Safina Center, which produces writings, films, and other artwork to convey the realities of what is happening to our world and the urgency of protecting it.

“It is more obvious than ever that information alone doesn’t work. People have to feel it,” Safina said.

In addition to protecting ocean wildlife, Safina has studied elephants closely, fighting elephant poaching in Africa. Photo: Julius Shivegha

In addition to protecting ocean wildlife, Safina has studied elephants closely, fighting elephant poaching in Africa. Photo: Julius Shivegha

Preserving Endangered Species and

Rainforests in South America

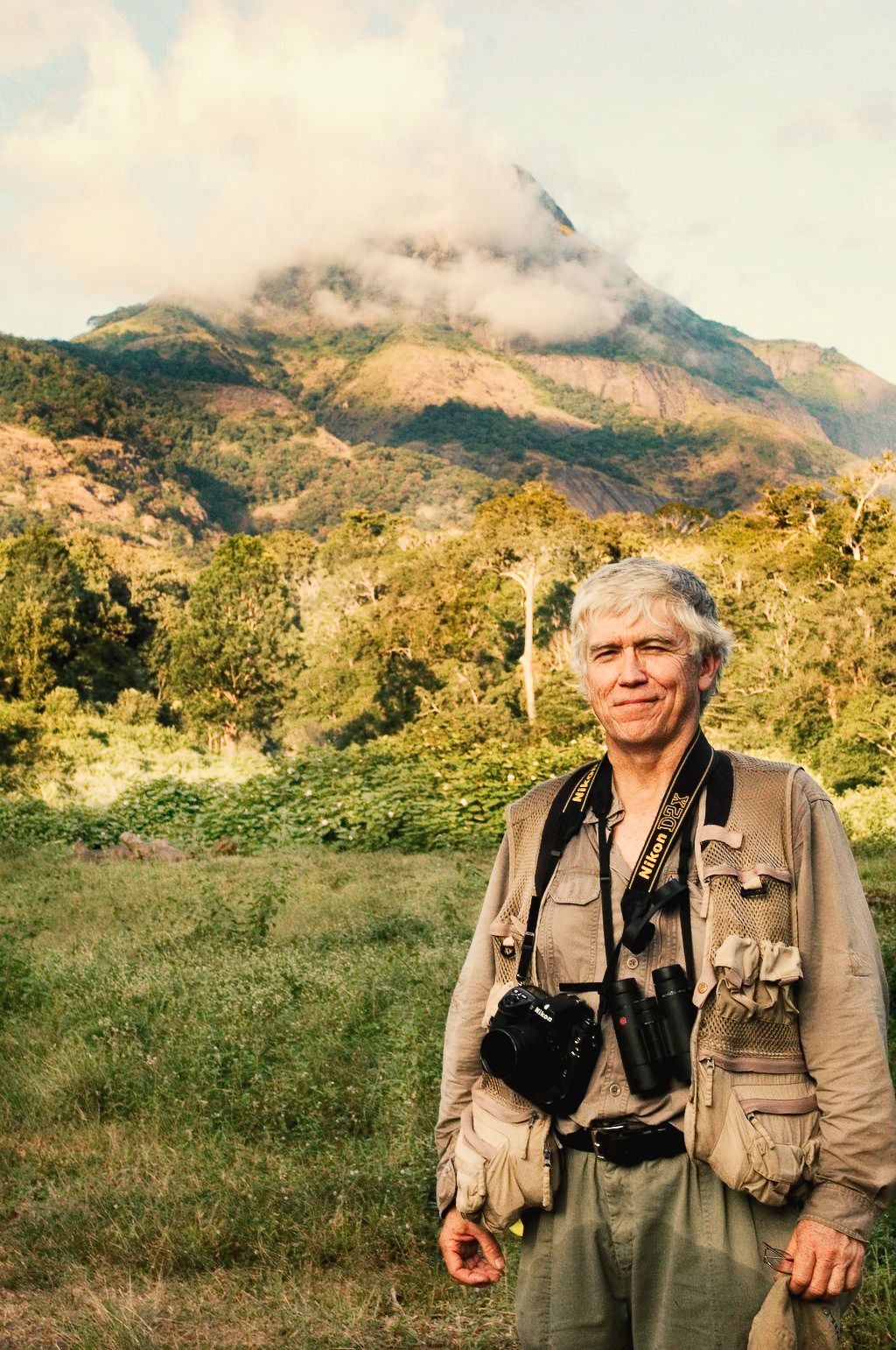

Russell Mittermeier, a leading expert in biodiversity, primatology, and tropical forest conservation, recognizes what needs to be done, and does it. Mittermeier, an adjunct professor in Stony Brook’s Department of Anatomical Sciences, has been affiliated with the University since 1978.

He is credited with protecting hundreds of threatened species and millions of acres of critical habitat, working closely with foreign heads-of-state and indigenous leaders across South America to promote biodiversity conservation in Brazil, Suriname, Guyana, French Guiana, and Venezuela. For more than 40 years, Mittermeier has chaired the International Union for the Conservation of Nature Species Survival Commission’s Primate Specialist Group, making primates a priority group for conservation worldwide.

A true pioneer, he has researched and described more than 20 species new to science. His concept of biodiversity hotspots remains one of the most important conservation developments in the last 25 years.

In 2018, Mittermeier was awarded the Indianapolis Prize, the most prestigious award in animal conservation, for his visionary leadership. Presented every two years, the prize carries a $250,000 award.

He has also held executive leadership positions at major global organizations, including Conservation International, Global Wildlife Conservation, and World Wildlife Fund.

Mittermeier has focused his field work in South America’s Amazonia and the Guiana Shield region, the world’s most pristine rainforest. Photo: Courtesy Global Wildlife Conservation

Mittermeier has focused his field work in South America’s Amazonia and the Guiana Shield region, the world’s most pristine rainforest. Photo: Courtesy Global Wildlife Conservation

Saving Endangered Species

in Madagascar

With Stony Brook’s commitment to global conservation, it’s no surprise that it recruited Patricia Wright, a world-renowned primatologist and expert on lemurs. In 2014, the Stony Brook professor of anthropology became the first woman ever to win the Indianapolis Prize. The award recognized her decades-long work saving endangered lemurs in Madagascar, for which she also received a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1989.

Her work in Madagascar began in 1986, when she was looking for the greater bamboo lemur, thought to be extinct. Not only did she rediscover that species, but she also discovered a new one: the golden bamboo lemur.

A testament to her passion and commitment to wildlife conservation, Wright helped establish Ranomafana National Park — a 106,000-acre protected area — an incredible feat that required five years of negotiations with village elders, government officials, and international aid agencies.

Madagascar is now home to over 110 species of lemur, compared with 32 when she started. In recognition of her invaluable contributions, the President of Madagascar awarded Wright the Knight of the National Order of Madagascar — the country’s highest honor.

Wright continues her work at Stony Brook’s Centre ValBio, a world-class research station that she founded on the edge of Ranomafana National Park. The center offers study-abroad opportunities to U.S. college students and research facilities for scientists and researchers.

Through Wright, Leakey, Safina, Mittermeier, and other trailblazing faculty, Stony Brook is transforming how today’s students and researchers perceive and interact with the natural world. Real change requires steadfast commitment and a multipronged approach. It requires training the next generation of conservation leaders and advocates. It requires holding policymakers and corporations accountable for their actions. And it requires shifting public opinion. In all these ways, Stony Brook is leaving an indelible mark on our world and all living beings that depend on it.

Thanks to Wright’s decades-long work, lemurs, the world’s most endangered mammals, are slowly resurging in Madagascar. Photo: Photo: Drew Fellman, copyright:2013 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Thanks to Wright’s decades-long work, lemurs, the world’s most endangered mammals, are slowly resurging in Madagascar. Photo: Photo: Drew Fellman, copyright:2013 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Global conservation and sustainability are just a few of the many ways that Stony Brook University is accelerating progress around the world. See how Stony Brook faculty are training the next generation of leaders and scientists, from building quantum communication networks to designing the next generation of materials — Stony Brook faculty are transforming their fields: