Restoring Public Confidence

in Higher Education

Highlights from the Midwest Innovation Leadership Forum

To win back more of the public’s trust, colleges should stress affordability, work harder to reach new types of students, and be more innovative.

INDIANAPOLIS

To counter plummeting public confidence in higher education, colleges and universities must rein in tuition, become more creative in helping students in need, and develop innovative learning experiences that reach more people.

Held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on August 26, the conference was co-hosted by Salesforce.org and Mitch Daniels, former governor of Indiana and president of Purdue University, the 80 attendees heard why many Americans have lost faith in colleges, and what they can do to restore it.

Several audience members, mostly college presidents and provosts from across the nation, acknowledged they had been reeling from polls and news reports that paint higher education as out of touch, overpriced, and concerned mainly with advancing its own interests.

Nationwide surveys show that among major U.S. institutions and industries, higher education has seen the greatest drop in public esteem. The shift follows party lines, with Republicans’ opinions dropping sharply. Prominent in the recent polls is a belief that college may no longer be worth its high price tag.

“The cost of college has outpaced basically everything else in the U.S. economy,” Jeffrey Selingo, a panel moderator and author who serves as Professor of Practice at Arizona State, said in an interview before the event. “Overlay that with the growing income inequality in society, and it creates the perfect storm for higher ed.”

In the past 30 years, tuition at private colleges has risen by 129 percent and by 213 percent at public institutions, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

A 2015 poll conducted by Gallup and the Lumina Foundation found that only 21 percent of the public believes higher education is affordable. Other polls show that fewer Americans believe that college is open and available to anyone who needs it.

The conference offered several insights into how to give the public more of what it says it needs colleges to be — more affordable, accessible, and open to innovative teaching.

Shrinking the College Price Tag

Among large public colleges, Purdue University is the exemplar for containing college costs. Since Daniels took over as president in 2013, Purdue has frozen its tuition rates, holding the line at just below $10,000 annually for in-state students. The university has also reduced its room-and-board fees by 5 percent and seen its student-borrowing rate reduced by one-third. More than 60 percent of Purdue degree-seekers graduate without student-loan debt.

Even as the university has become more financially accessible, the average grade of its students has gone up. “We want to be both excellent and as inclusive as we can be,” Daniels said.

Purdue students also graduate at a higher rate than the average bachelor’s or master’s degree seekers elsewhere, possibly because Purdue has worked to foster affordability. “We have better completion rates than community colleges do with A.A. degrees, which bucks the national trend,” Daniels said.

Students in 70 percent of Purdue’s programs have the opportunity to graduate in three years, potentially saving them one year of college costs.

Daniels urged college leaders “to look for better economies” and similar opportunities for cost savings within their institutions, while making affordability the cornerstone of what they do.

Other panelists noted that ongoing tech developments—online learning, new types of micro-credentials, innovative ways to amass and analyze data—may help colleges hold their prices down during a time when workforce education needs are exploding.

But to get to that point, colleges must embrace a new model.

“Disruption can lead to more accessibility and affordability,” said Alana Dunagan, senior research fellow at the Christensen Institute. “But we can’t afford a system that serves as a sorting structure that separates the wheat from the chaff, as we’ve been doing. We need one that can be accessible and affordable for all Americans, and can move them all forward.”

Mitch Daniels, President of Purdue University

Mitch Daniels, President of Purdue University

Helping Students Pay

Besides controlling tuition costs, colleges can help more needy students get to college by finding new ways to help them pay for it. Higher education is increasingly falling out of favor at a time when student debt nationwide has mushroomed to $1.5 trillion. Lowering that amount calls for new solutions.

Some panelists touted the potential of income share agreements—or ISAs—as an alternative to the traditional student-loan arrangement. Under an ISA, students and the school enter into a contract that gives a student the money they need to attend. The students will then pay back a percentage of their salary after they find work, post-graduation. Typically, the amount a student pays back increases as their salary rises.

Such agreements can help colleges do away with inequities centered on race and family income. Black students receive $5 billion less in student aid than whites each year, said Kevin James, Founder and Chief Executive at Better Future Forward, a nonprofit that works to link lower-income high schoolers with college opportunity.

“We are dramatically underinvesting in the students who can use the most help,” James said.

And yet, low-income black students who do receive loans pay them off at a slower pace and are more likely to default than whites. Those factors, plus the pressure finances can put on a student’s ability to stay in school, have resulted in a crisis.

When members of one panel were asked to outline the one thing they would have colleges do to improve, they agreed that providing more financial support to those students is paramount.

Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, added that colleges must “stop ignoring race. There’s a crisis of success for African-American students. We need to focus on that.”

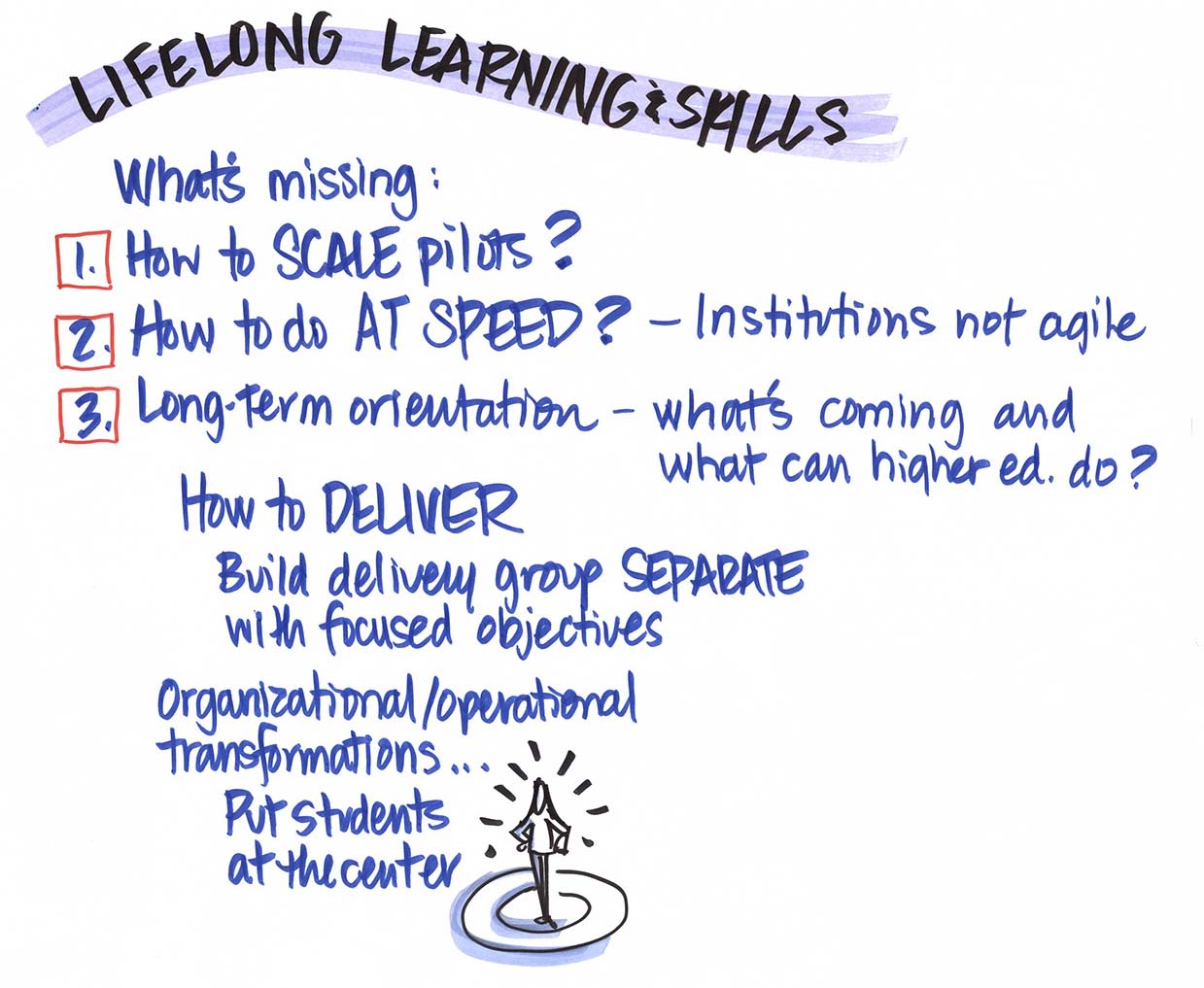

Emphasizing Lifelong Learning

Some conference speakers said colleges could increase their standing with the public by giving more staunch support to lifelong-learning programs.

Some university presidents, such as Joseph Aoun at Northeastern University, encouraged other institutions at the 2018 New England Innovation Leadership Forum to create new ways for adults to get the credentials and skills they need in order to fuel an economy driven by artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies. Those credentials shouldn’t be limited to college degrees, and should be more easily attainable for people in mid-career.

Serving that segment of the workforce will be vital to a college’s success, several panelists said. It will also address a burgeoning need: “The demand for talent is the highest it’s been since forever,” said Jamie Merisotis, President and Chief Executive at the Lumina Foundation.

Others pointed out that colleges are uniquely positioned to help companies bridge a “skills gap” for many of their employees, including those who already have college degrees. “We’re hearing from companies that they need opportunities for workers to gain more skills and competencies,” said Dane Linn, Vice President for Immigration, Workforce, and Education at the Business Roundtable.

To take advantage of such needs, university leaders will need to recognize that the definition of higher education is in flux.

“The big change we’re witnessing and the reason we need to innovate is that the type of student we serve is changing,” Mitchell said. “Yet our model is based around what our institutions can do with 18- to 22-year-olds from similar backgrounds and with similar career aspirations. There is a wealth of students and learners we haven’t really thought to reach.”

Efforts to make sure Americans can affordably upgrade their skills without getting college degrees have been touted as a way to keep colleges robust during the coming years, when the numbers of traditional, 18- to 22-year-old students attending their institutions will likely decline.

Lifelong learning “is staring us in the face,” Mitchell said in an interview conducted before the event. Yet too few institutions have pivoted toward what will likely be a new era for colleges.

“Tons of people hated it when Purdue absorbed Kaplan [an online learning company, in 2017],” Mitchell added. “Yet, that move has provided Purdue with the infrastructure with which to offer more lifelong learning to a wide range of people.”

Purdue converted Kaplan into Purdue Global. In its first year, Purdue Global helped to teach 30,000 people online, expanding the university’s reach, while making education more accessible and affordable. What’s more, its focus is on lifelong learners and people upgrading their skills.

Carol D’Amico, Executive Vice President of the Strada Education Network

Carol D’Amico, Executive Vice President of the Strada Education Network

Overcoming a “Disconnect”

Low college-completion rates, universities’ resistance to accepting transfer credits from other institutions, and a sense that the admissions system is rigged have further shifted public opinion against colleges. Yet institutions have done too little to respond, some speakers said.

Despite public sentiment showing that only one in eight Americans thinks higher ed is doing a good job, 90 percent of colleges and university personnel surveyed “think we’re doing just great,” said Carol D’Amico, Executive Vice President of the Strada Education Network. Those results, from a survey conducted by Strada and Gallup, show “a huge disconnect” between how college leaders think they are doing and how the nation sees them.

Other research D’Amico shared found that 50 percent of recent grads are underemployed, 60 percent of current students are working at jobs, and 70 percent have attended multiple institutions—a statistic that puts the transferability of credits into sharp relief.

Such metrics show that the era of “the traditional learner” is ending and that colleges need to expand their definition of what a learner is, she added, using the term “consumer” instead of “student.”

“Colleges need to allow consumers to be more precise about what they want,” D’Amico said. “We need new on-ramps and off-ramps for their college experience, new ways to get them education when and where they need it.”

Innovation is a Must

More than anything else, colleges need to overcome their aversion to change, other speakers said. As every facet of the U.S. economy undergoes transformation, colleges should expect to do the same.

“If there’s one sector that needs to try new things, it’s ours,” Daniels said. “Our world is populated by those who see themselves as smart and progressive, but we’re as reactionary an institution as I’ve ever seen.”

Taking smaller steps to reach more students can lead to strong results, he added. Colleges shouldn’t shy away from experimentation because of the effort it requires.

“There’s a real responsibility to try new things,” Daniels said. “In a sector that is resistant to change, you don’t have to do much to look like Thomas Edison.”

As colleges work to develop a better-educated workforce, Salesforce.org looks for fresh ways to collaborate with them toward that goal, said Rob Acker, CEO of Salesforce.org.

“We know that education is the great equalizer,” Acker told attendees at the Midwest Innovation Leadership Forum. “We need to partner better with colleges to overcome their challenges.”

Salesforce.org, the dedicated social impact team of Salesforce, delivers technology to 42,000 nonprofits, educational institutions, and philanthropic organizations so they can connect with others and do more good.

Salesforce has given $298 million in grants toward local communities, with a focus on education and workforce development. The company also donates highly-skilled labor, giving its employees seven paid days off each year so they can volunteer to better their communities.

“Salesforce employees have volunteered more than four million hours — and a major focus area is in education,” Acker said, adding that the company aims to make colleges work more efficiently and effectively as they seek to improve affordability and accessibility. “Our employees work to address educational challenges at the tech level."