Indiana University is fighting online misinformation to protect democracy

An informed electorate is the foundation of a strong democracy. But how can we ensure that false information doesn’t weaken or destroy that foundation?

The risks posed by the growing spread of misinformation online were evident last year when a vast army of online “bots” – automated accounts designed to look like real people – sprang up on Twitter to push messages on the eve of the midterm elections, discouraging voters from going to the polls. Ultimately, Twitter deactivated the accounts – a staggering 10,000 in total.

Another sign of the threat’s seriousness: California has become the first state in the nation to regulate bots. A recently passed law requires automated accounts to clearly disclose their artificial identity when they are used to sell a product or influence a vote.

The common thread in these responses? Indiana University.

An interdisciplinary approach to a pervasive problem

IU’s Observatory on Social Media, which recently received a $3 million investment from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, was the source of both the technology used to detect the vote-suppressing bots and the research used to inform the state law. The observatory is a partnership between the IU School of Informatics, Computing and Engineering; the IU Network Science Institute; and The Media School at IU.

In the case of the California law, the bill’s drafters cited research from the observatory in documents used to inform the bill’s debate in the state senate and assembly. In the case of voter suppression, Twitter shut down the fake accounts after being notified by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, which was using a system built largely from technology created by the observatory.

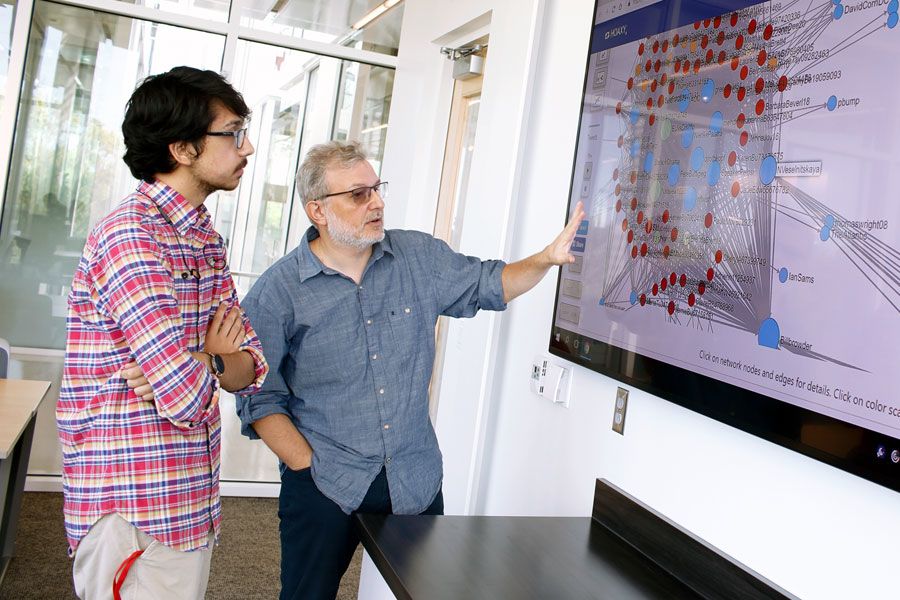

This technology has since been expanded by IU data scientists into a tool called “BotSlayer,” which can quickly raise an alarm when a large group of bots starts “astroturfing” – pushing out messages in a coordinated manner to mimic legitimate grassroots political activity. Among the observatory’s many beta testers quietly using this technology to monitor against election interference are The Associated Press, The New York Times, CNN, the Democratic National Committee and the Office of the House Majority Leader.

“The digital experience of our democracy is vast, uncharted territory. This observatory will help researchers peer into the unknown for insights that can inform the future of our democracy.”

Sam Gill, vice president for communities and impact at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

An ever-evolving challenge

Yet the tool is but one small step in the constant arms race against online misinformation, according to Filippo Menczer, an IU professor of informatics and computer science and director of the Observatory on Social Media.

“Whether we like it or not, social media have become the main way that people access news today,” Menczer said. “If some group can manipulate people’s opinions, they can manipulate democracy. If they can flood a social platform with misinformation, they can suppress speech by drowning out the real voices.”

More than a decade ago, Menczer saw the battle lines forming in the coming fight against online deception. As an experiment, he created a website that randomly generated celebrity gossip news, labeled it as fake and put ads on the site. A month later, a check arrived in the mail.

“That was when I first realized how easily someone could monetize false content,” he said.

The rise of the misinformation bots

Fast forward 10 years, and major news organizations have run headlines about Macedonian teenagers who made fortunes producing stories fabricated to stoke partisan rage in American voters. The U.S. Department of Justice has indicted over a dozen foreign individuals with conspiracy to defraud the United States through online activity during the 2016 election. The CEOs of Facebook and Twitter have been called before Congress to testify about how misinformation spreads on their platforms.

“By joining together experts in journalism and data science, we’re not only able to identify the most significant questions about how information and technology can be manipulated to weaken democracy, but also to design and build the sophisticated tools required to attack these questions.”

Menczer’s work has also had a brush with the internet misinformation machine. In 2014, a partisan website twisted the observatory’s research into a grand conspiracy about government attempts to suppress free speech.

In reality, the observatory is a nonpartisan effort to create open-source tools to understand how information spreads online and identify accounts that purvey misinformation. The project has attracted millions in federal funding, produced over 70 academic publications and generated more than 460 news stories across the globe. One of its most popular tools, a bot-detection algorithm called Botometer, fields hundreds of thousands of queries per day.

A new phase on the horizon

Now, the observatory stands poised to enter a new phase through its partnership with The Media School. Over the next several years, the center will roll out more new tools, provide more support to outside groups who want to use their technologies and implement a data journalism program. It will also investigate thorny subjects such as the technological forces behind mistrust in media and the growing challenges of identifying trustworthy sources of information.

“This new center comes at a time when there has never been more confusion about news – its sources, its accuracy, its effect on the public. Bringing journalists and students into contact with the best technology for assessing news legitimacy and accuracy will be an important step forward in the evolution of journalism in a new media environment.”

“By combining expertise from computer scientists and journalists, this center will provide reporters with the tools and insights they need to conduct their work responsibly, and policymakers with evidence-based insights to inform the debate about regulating social media platforms,” said Betsi Grabe, a professor at The Media School and a co-leader on the observatory.

“The problem of misinformation isn’t going away anytime soon,” Menczer added. “But if we can keep pace with those who purvey it, we may be able to increase the cost of their attacks so much that fewer can carry them out – and eventually reach a point where, like email spam, almost no one ever sees it.”