Sparking hope for a 'hopeless' disease

How Indiana University is expanding its

Alzheimer's research pipeline

When Anita Harden’s father started forgetting things, she knew to suspect Alzheimer’s disease.

She knew the signs—memory loss, changes in personality, getting lost or misplacing belongings—because she had already seen them in her mother, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s five years earlier.

But this time was different, too.

Although her father’s diagnosis was just as challenging as her mother’s, Harden was glad they’d caught the disease early. And now that she was more familiar with Alzheimer’s care, Harden was ready to take advantage of the world-class scientific talent at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis—a leader in Alzheimer’s research, where neuroscientists were conducting a clinical trial for a new Alzheimer’s treatment. Harden enrolled her father in the study with the hope of slowing his disease’s progression.

“We went over to IU for two years straight because I had to be involved as his caregiver,” she said. “I found out later—two years after the study was over—that he was not part of the placebo. I could see a difference.”

For Harden, that difference meant more valuable time and conversations with her father, Louis, whose memory and cognitive ability improved while he was participating in the clinical trial, she said.

“The results lasted for a while,” Harden said. “Even after the study was over, it probably slowed his decline for another year or two.

“It felt good that maybe I had a little bit longer with him.”

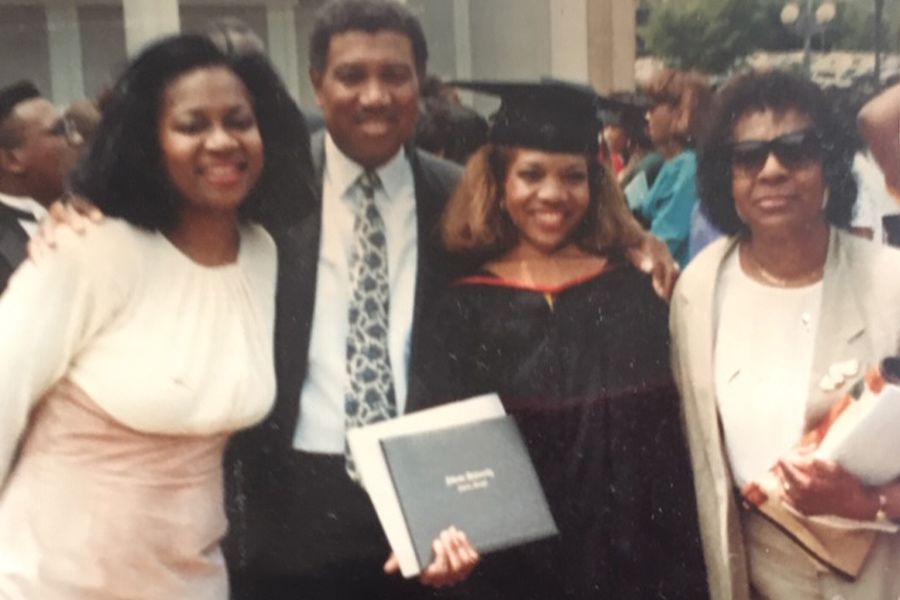

Anita Harden, left, spent more than a decade serving as an Alzheimer’s caregiver to both parents, pictured during a family graduation. She is one of 16 million unpaid Alzheimer’s caregivers in the U.S.

Anita Harden, left, spent more than a decade serving as an Alzheimer’s caregiver to both parents, pictured during a family graduation. She is one of 16 million unpaid Alzheimer’s caregivers in the U.S.

“Unlike a physical disease, Alzheimer’s feels different because you’re dealing with someone’s mind. At first, it’s hard for the person who has Alzheimer’s, but after they become so far gone, it becomes hard on the caregiver.”

Anita Harden, a caregiver for her parents, who died of Alzheimer’s disease

A growing problem for an aging population

Today an estimated 5.7 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease. It is the fifth leading cause of death for U.S. adults aged 65 years and older, and the sixth leading cause of death for all adults in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Alzheimer’s involves parts of the brain that control thought, memory and language. It is particularly devastating because, over time, it can seriously affect a person’s ability to carry out daily activities and connect with their loved ones.

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s and the causes of the disease are unknown, but age is the best-known risk factor.

By 2050, as baby boomers age and medical advances help humans live longer, the CDC estimates the number of people living with Alzheimer’s will grow to 15 million. The financial burden of the disease is expected to rise in lockstep, with Medicare and Medicaid spending on people with Alzheimer’s estimated to quadruple to nearly $1 trillion by 2050.

“Those are the numbers that make you realize we need to do something, and we need to do it soon,” said Bruce T. Lamb, executive director of the Stark Neurosciences Research Institute at the IU School of Medicine. “So how do we help speed up that process? How do we get things that will be beneficial to people as fast as we can? That’s really the goal in terms of when we're setting up new projects and programs.”

A broad approach to a complex disease

Over the past three decades, IU has made big investments in its neuroscience research programs, partnerships and capabilities from basic science to clinical implementation.

With the fall 2019 launch of a new Alzheimer’s drug discovery center funded by the National Institutes of Health, Indiana is home to one of the most comprehensive Alzheimer’s research programs in the country, including several initiatives that play a key role in national efforts to study the disease.

The IU School of Medicine currently ranks fifth among U.S. medical schools in funding from the National Institute on Aging, the NIH branch that is the primary funder of Alzheimer’s disease research. In fact, four of the school’s top five NIH-funded research grants are focused on studying Alzheimer’s disease.

The aforementioned drug discovery center—one of only two centers of its kind in the country, as selected by the NIA—aims to identify the best drug targets for Alzheimer’s by testing a list of potential molecular candidates compiled by researchers nationwide.

The challenges of finding effective medicines for Alzheimer’s disease are numerous and complex. It is going to require a very strong ecosystem that is enriched with scientific diversity and new collaborative models. The emergence of centers like this, which can not only perform cutting-edge science but also inform the community with results, are going to be important partners with all groups who are committed to creating breakthrough therapies.

IU researchers also lead:

- The largest and most extensive study of patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

- A national consortium focused on developing the next generation of animal models for Alzheimer’s disease, which mimic the human disease for study and are used by Alzheimer’s researchers around the country.

- The national repository where biological samples such as DNA, blood and cells are stored and made available for new and ongoing dementia research locally and around the world.

Additionally, IU’s Indiana Alzheimer Disease Center, which was founded in 1991, is one of 32 centers working together across the U.S. with a sole mission to advance Alzheimer’s research.

All of this adds up to the kind of robust translational research program necessary to take on a disease like Alzheimer’s, Lamb said.

“One of the things that's really changed in my career in science is how much more of what we do now is team-based,” he said. “We need big teams who bring in a lot of different people with a lot of different expertise. No one person can do it all.”

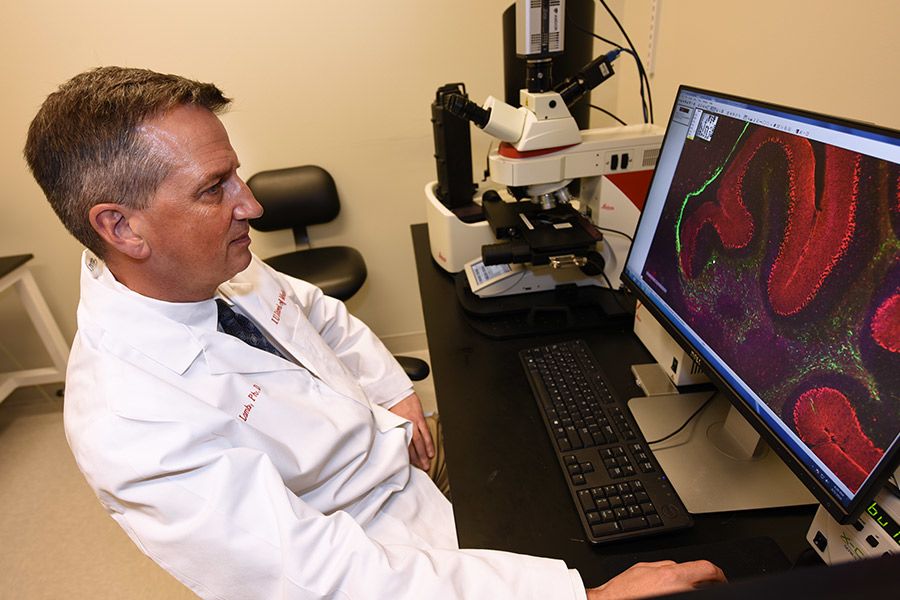

Bruce T. Lamb leads MODEL-AD, a national research consortium centralized at the IU School of Medicine that works to develop animal research models for testing potential Alzheimer’s therapies.

Bruce T. Lamb leads MODEL-AD, a national research consortium centralized at the IU School of Medicine that works to develop animal research models for testing potential Alzheimer’s therapies.

“Right now is a critical time for Alzheimer’s disease research. As a result of NIH investments in our programs and infrastructure, IU School of Medicine has all of the components needed to make major contributions to the field.”

Bruce T. Lamb, executive director of IU’s Stark Neurosciences Research Institute

A team effort for a healthier future

It’s not only doctors and scientists who are needed to help find a cure for Alzheimer’s disease.

Lamb said researchers struggle to recruit Alzheimer’s patients, as well as healthy people, for clinical trials related to the disease—something he attributes to feelings of hopelessness often associated with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

“It’s a really difficult subject when you don’t feel there’s something on the horizon that’s going to help you,” he said.

But for Anita Harden, those feelings changed when she saw the progress her father made while participating in Alzheimer’s research.

“The fact that I saw an improvement lets me know that we are getting closer,” said Harden, who has since enrolled herself in IU research studies of healthy brains and has arranged to donate her brain to scientists at the IU School of Medicine after her death.

“I have a certain comfort in knowing that if something is ever discovered with me and my brain, that IU is there for me to participate in further studies,” she said.

“IU is working on all ends of the spectrum: prevention, cure, maintenance—the whole bit. That gives me a lot of hope.”